Developing European Library Services in Changing Times

Abstract

The purpose of this article is to explain what academic and national libraries can do to continue to offer services and facilities at a time of economic difficulties. It identifies a number of methodologies and opportunities that are open to libraries and takes the view that it is never wise to waste a good crisis, because all threats are really opportunities in disguise.

The kernel of this paper was delivered at the 10th Anniversary special EISZ Consortium Members’ Meeting on 2 December 2011, in Budapest, Hungary. It builds on an earlier talk delivered in Thessaloniki, Greece, on 14–15 November 2011 at the 20th Pan-Hellenic Academic Libraries Conference, entitled ‘Academic Libraries and Financial Crisis: Strategies for Survival’. Both these presentations are available in UCL Discovery.

This article draws on themes used in both presentations, and introduces a new one on the topic of copyright reform. The article looks at the initial economic context for European research libraries and then examines ways in which libraries can tackle the threats which the current financial crisis poses. Joint procurement is one way in which libraries can achieve value for money, and the paper examines the role of JISC Collections in the UK. Innovation through collaboration and shared services are also ways in which libraries can innovate/make savings in a cost-effective way by sharing the burden of costs around the partnership. The paper gives two examples: one which is now well established, the DART-Europe portal for Open Access e-theses; and one which is in the early stages of being discussed — a cloud-based solution for true collaborative cataloguing amongst the UK’s research and national libraries. The European Research Area (ERA) and the contributions that libraries can make to this infrastructure through innovative EU project funding are analysed in some detail by looking at LIBER’s EU project portfolio. Finally, change and growth can come through changes to legal frameworks, and the paper looks at the Hargreaves review of copyright frameworks in the UK and the launch of the new library-based EU lobbying group for copyright reform, Information Sans Frontières (ISF).

The context

2011 has not been a happy time for European budgets and, at the time of writing, the Eurozone countries face fresh turmoil.[1] University funding is not immune from these changes in European society and, certainly in the UK, university libraries are experiencing cuts in recurrent funding. My own library has seen cuts of 13% over three budget years, with further annual efficiency gains expected. What avenues are open to libraries in situations like this to help them continue to offer services to support teaching, learning and research?

Joint Procurement

One avenue that is open to libraries is the possibility of undertaking joint procurement for content in a consortial setting — the reasoning being that there are savings to be made when a large number of players come to the table together to purchase content. In the UK, all Big Deals are negotiated for UK universities by JISC Collections. In 2010–11, JISC Collections realised £50 million in efficiency savings for British universities.[2] At a time of financial crisis, hard negotiations with all suppliers are expected. The current JISC model is an opt-in model, where JISC Collections negotiates on behalf of its members and then asks its members whether or not they wish to accept the deal. This is not the easiest way of negotiating, as the procurement team does not know (at the time of negotiation) how many libraries will sign up to a deal. This makes it a challenge to obtain the best value for money for libraries. However, the model does reflect the autonomy of UK universities in that they themselves make the final decisions over expenditure.

The current challenge with Big Deals is not the Big Deal model itself, but the amount actually charged for deals.[3] The benefits of the Big Deal are obvious:

-

Desk top access to large amounts of scholarly material — and academics are certainly not going to complain about that opportunity

-

Libraries welcome the model because of greater access and small libraries particularly benefit through access to a large number of titles which previously they could not afford

-

Large publishers like it because it reduces attrition, resulting in additional e-fee income, locking libraries into multi-year agreements with built-in annual price increases.

In 2008, the JISC Journals Working Group commissioned Evidence Base to evaluate NESLi2 Big Deals in comparison with a title-by-title selection. They found that not only were the deals good value, in that previously unsubscribed titles were well used, but also that access to the Big Deal seemed actually to stimulate use.

However, there are disadvantages. In a Big Deal, libraries are unable to shape collections. There is less flexibility to respond to budget cuts: ‘In Britain, 65% of the money spent on content in academic libraries goes on journals, up from a little more than half ten years ago.’ Economist, May 26th, 2011.

Some content is not used and some journals in a deal are more valuable than others. There are difficulties in small journal publishers and monograph publishers being able to sustain sales in this environment, which in turn increases the market power of a small number of large publishers.

In a survey of a number of other business models Lorraine Estelle, the Chief Executive of JISC Collections, has concluded that no other business model currently challenges the predominance of the Big Deal. The high cost of journals is a consequence of continual increases in the number of articles published each year, the uncompetitive nature of the market place, and the result of market power. The academic community will face these issues irrespective of the business model.

Innovation through collaboration

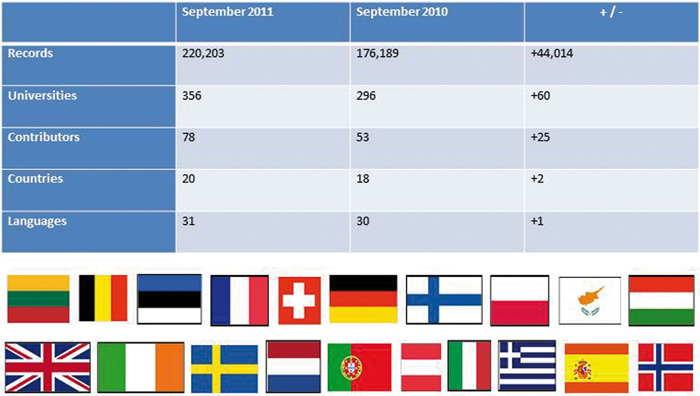

Cutting costs through collaborative purchasing is one way to save money. Another way to support services is to innovate through collaborative partnerships, where the costs of development are shared around the membership. A good example of this sort of development is the DART-Europe portal, which gives access to European Open Access research theses. At the time of writing, the portal indexes 254,641 full-text research theses from 379 universities sourced from 20 European countries.[4] The portal is run by UCL (University College London) on behalf of LIBER members and the partnership commenced in 2005.

A new Report from the ERAC (European Research Area Committee) on National Open Access and Preservation Policies: Analysis of a Questionnaire to the European Research Area Committee appeared at the end of 2011.[5] It is a pan- European analysis of the state of play in Open Access and Digital Preservation, with the analysis being taken from answers to a questionnaire distributed in 2010 to all ERAC members and observers. The Commission received 29 responses between 21 December 2010 and 11 March 2011: 25 from EU Member States (Bulgaria and Hungary did not respond) and four from ERAC Observers (Iceland, Montenegro, Norway and Switzerland). In the area of Open Access, the Report notes that there has been significant work done on research theses. The DART-Europe portal is highly commended in the Report and is referenced explicitly in sections 1.4.2 and 1.5.5 as a model of good practice.

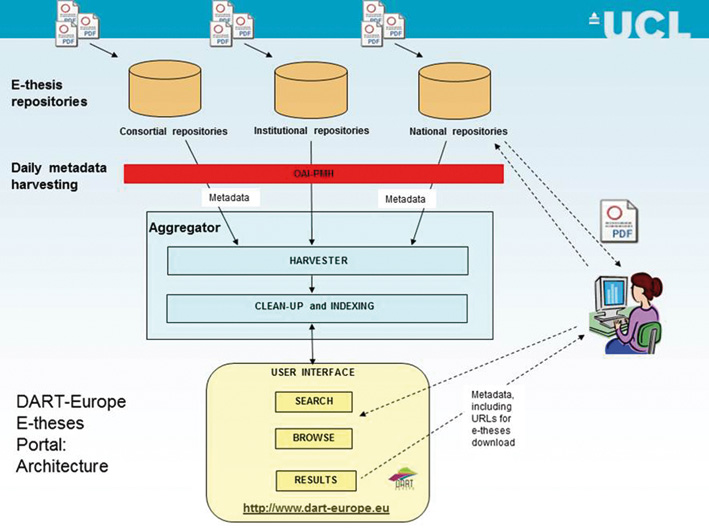

How was this work accomplished and what business model supports the development? The architecture which supports the service is portrayed in Figure 1. There are essentially three layers to the service — a storage layer (at the top of the Figure, usually Open Access repositories based in institutions), a harvester and a service which normalises the data (based in UCL), and the public portal (also based in UCL). Only metadata is harvested, not the full text of the thesis. The full text remains on the local server and the metadata points to it from the portal based in UCL.

The partnership and business models which underpin this service are important and are a significant part of the reason why the models are successful. The partnership model is based on the 400+ members of LIBER (Association of European Research Libraries).[6] Partnership in the DART-Europe portal is based on the LIBER membership. There is no separate fee for contributing metadata to the DART-Europe portal. The ability to be a partner in the DART-Europe partnership for free is one of the benefits of LIBER membership. All partners are invited to sign a partnership agreement,[7] which outlines principles and values which the partners espouse. The first two principles cover how the partners contribute metadata to the portal:

-

‘DART-Europe will encourage the creation, discovery and use of European e-theses, and will maintain a central Portal for e-thesis aggregation and access.

-

‘European libraries and consortia are invited to contribute metadata to the DART-Europe Portal. Contributors will determine the terms and conditions under which their metadata are contributed.’

The business model is covered in the third of the principles in the partnership agreement:

-

‘DART-Europe welcomes the contribution by partners of resources to support the management, discovery, usability and preservation of e-theses, and to further the aims and objectives of DART-Europe.’

What this means is that the costs of running and developing the portal are met by UCL, and the costs of contributing metadata to the portal are met by the individual partners, usually by work in kind in their technical departments. There is no cross-subsidy from LIBER for maintaining the portal — LIBER membership fees do not subsidise LIBER services, which are meant to be self-funding. Development work on the portal is currently funded by UCL as part of its own programme of IT development. It is an unusual business model, and it is not clear how scalable it is to other services. What underpins the partners’ commitment to maintain and develop it, however, is the impact that access to European research theses has on those who use them.

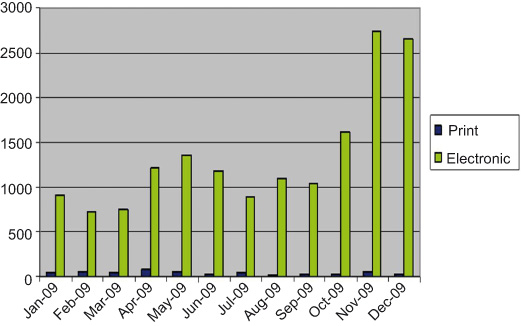

Figure 2 shows the results of a comparative study in Dublin City University, a DART-Europe partner, of the use made of paper theses stored in their library and digital theses in the institutional repository.[8] The number of print loans includes all print theses stored in the library (almost 30 years). The number of e-thesis downloads accounts for only the theses that have been added to the institutional repository (less than 2 years). The figures speak for themselves. There were 518 print thesis consultations in 2009, compared to 16,212 electronic thesis visits. The conclusions these statistics suggest are supported by comments which are e-mailed to the DART-Europe e-mail address by users who have used the service. To pick just one at random: ‘I really appreciate this project, it is very nice to be able to have access to so many documents.’ — Sebastian, France.

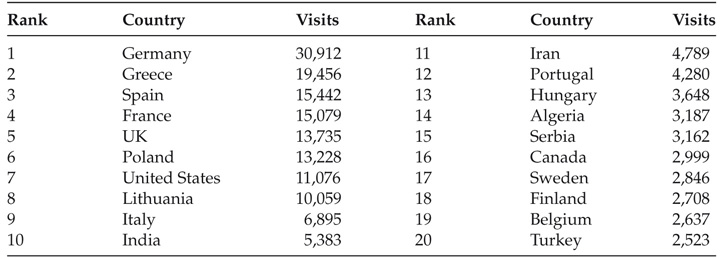

The most popular countries from which the calls to the DART-Europe portal were made were:

The success of the DART-Europe portal shows that it is possible to innovate through collaborative partnerships to add value to the end-user experience. The keys to its success are the partnership model, which underpins the consortium, and the shared values in wanting research theses from Europe’s universities to gain the maximum possible visibility in a networked environment.

Shared Cataloguing: the Next Generation

2011 saw much activity in RLUK, the UK consortium known formally as Research Libraries UK.[9] The 2009 Research Information Network (RIN) Report Creating Catalogues: Bibliographic Records in a Networked World[10] found that the current arrangements for producing and distributing bibliographic data for both books and journals involve duplications of efforts, gaps in the available data, and missed opportunities: ‘...[T]here would be considerable benefits if libraries, and other organisations in the supply chain, were to operate more at the network level.’

The RLUK Report, presented at the RLUK Members Meeting in London in December 2011, and currently being further studied by the RLUK Board, used the RIN conclusion as the starting point for a broad overview of current cataloguing activities and services in RLUK libraries. The Report, for which I had the honour to chair the Working Party, recommends that RLUK metadata is released as Open Data and that RLUK develop a more rigorous position on Linked Data, which would allow structured data to be linked on the web.

Were such changes to take place, the library catalogue would become re-positioned in terms of its relationship to the wider context of the web, and the social network of links that the web represents. The drivers for considering such developments are potential cost savings by RLUK members and a better service for users.

The Report identified that the best solution was for a cloud-based implementation to stand in for both local and central management of systems. This would allow local library management functions and a centrally shared metadata catalogue (community zone).

Metadata issues will need to be addressed: duplication of records for the same item needs to be replaced by the concept of a Master record.

The RLUK databases (COPAC,[11] for public access and the record retrieval service for copy cataloguing) need to be re-positioned in the wider context of the web. Coverage certainly needs to be expanded to include new media types, e.g., blogs, wikis, Open Access content, and e-books. A truly shared cataloguing service would reduce the footprint of local library management systems and it would re-define how libraries work.

The Report made a number of top-level recommendations for RLUK to consider further:

-

that funding is identified to investigate the requirements and feasibility of a shared UK cataloguing service

-

to co-sponsor with the JISC (Joint Information Systems Committee) a full cost-benefit analysis of providing an overall, above-campus, shared cataloguing system solution.

In the light of the 2009 RIN Report, and of the potential for network developments to transform the way that libraries work and the services they offer, the Report offers an exciting and challenging way forward for libraries to re-position themselves in the information landscape, with possible budget savings as a result.

European Research Area — Libraries as Part of the European Research Infrastructure

A particular area of work for LIBER is raising awareness amongst EU institutions of the potential for Europe’s research libraries to play a bigger role in Europe’s research infrastructure, and to be funded for this role.

At the LIBER Annual Conference in Barcelona in 2011, Commissioner Neelie Kroes acknowledged the role that LIBER is playing in helping to create a new information research infrastructure in Europe. She also set the ambitious target that the whole of Europe’s cultural heritage should be available in digital form by 2026.[12]

One way that libraries can gain new income is by bidding for European projects. Unlike other funding agencies, the European Commission is significantly ramping up funding for research and innovation over the next 10 years — the proposed budget for Horizon 2020 (successor to the current funding programme, FP7) is €86 billion, an increase of 46% compared to the current programme.[13]

This is a lesson that LIBER is learning. LIBER has 420 members from across Europe and is a source for network building and collaborative partnerships. LIBER now has a full-time EU Projects Officer and, from January 2012, an EU Projects Communication Officer. The current LIBER EU projects portfolio has grown from zero in the last three years. European projects in which LIBER is/has been involved, are:

-

Europeana Travel — a digitisation project, which finished in May 2011, with 1,000,000 digital objects on the themes of travel, tourism and exploration being made available to the Europeana portal.[14]

-

Europeana Libraries — LIBER’s biggest EU-funded project to date at €4,000,000. Output will be a new aggregator for metadata and full text from Europe’s research libraries into Europeana. 5,000,000 new digital objects from research libraries will be made available in Europeana by 2012.[15]

-

APARSEN — looking at the start of preparations by stakeholders across Europe for digital curation. Builds on LIBER’s input into the US Blue Ribbon Taskforce on Economically-Sustainable Digital Curation.[16]

-

ODE — Opportunities for Data Exchange. Looking at the level of preparation in Europe for research data curation and re-use. LIBER will manage the input of European research libraries.[17]

-

Newspapers Online — a project which starts in January 2012 with the aim of adding 29 million pages of European newspaper content to Europeana.

-

MedOANet — starting in December 2011 with the aim of facilitating Open Access policies and strategies in Mediterranean and neighbouring countries; kick-off meeting in Athens in January 2012.

-

AAA — a technical project looking at (amongst other things) the opening up of computer networks across European borders which will allow researchers away from their home university access to their subscribed digital content.

For all LIBER’s confirmed projects, and projects under consideration, the income for the LIBER Foundation alone is €521,597. This is new income, which would not otherwise be available to LIBER. The purpose behind LIBER’s bidding for such funding is to embed research libraries into the European research infrastructure. An issue is always the percentage of total costs which the Commission will pay. LIBER will only bid for projects which are 75%–100% funded. All LIBER members can become partners in LIBER projects, and the LIBER membership fee is a maximum of €425 per year.[18]

Pushing Forward the Borders

LERU is the League of European Research Universities,[19] an association of 21 leading research-intensive universities that share the values of high- quality teaching within an environment of internationally competitive research. Founded in 2002, LERU is committed to:

-

education through an awareness of the frontiers of human understanding

-

the creation of new knowledge through basic research, which is the ultimate source of innovation in society

-

the promotion of research across a broad front, which creates a unique capacity to re-configure activities in response to new opportunities and problems

The purpose of the League is to advocate these values, to influence policy in Europe and to develop best practice through mutual exchange of experience. LERU regularly publishes a variety of papers and reports which make high-level policy statements, provide in-depth analyses and make concrete recommendations for policymakers, universities, researchers and other stakeholders.

One of the areas in which LERU has begun to work, is Open Access. A general meeting of LERU Chief Information Officers/University Librarians took place in UCL in London in December 2009. That meeting appointed a Working Group to draw up a LERU Roadmap towards Open Access. The Roadmap was considered twice by LERU Vice-Chancellors at meetings in London and Paris and it was launched in Brussels on 17 June 2011.

The purpose of the Roadmap is to offer guidance on how to position a university in the European Open Access landscape. It builds on the Open Access Statement of the European Universities Association[20] and is a Roadmap for all European Universities, not just LERU members. The Roadmap[21] offers advice on the following issues:

-

Open Access in a wider context: Open Scholarship and Open Knowledge

-

The Green route for Open Access — Steps to Take

-

LERU and the Gold route for Open Access

-

Models of Best Practice to support the Roadmap

-

Benefits for researchers, Universities and Society

The two basic mechanisms through which researchers can make their work freely available are often termed as the ‘gold route’ and the ‘green route’. The adoption of either or both routes could lead to a transformation in the means of disseminating research outputs by LERU and other universities across the globe.

LERU and/or other universities can consider having Open Access repositories into which, copyright permissions allowing, copies of their members’ research outputs could be deposited. Those who already have such repositories are continuing to develop them. Many universities have found the Green route a helpful one to follow as a means of improving the dissemination of research outputs. In Webometrics listings of the impact of institutional repositories, LERU universities are significant contributors. The July 2010 listing showed that five of the top ten European universities listed are members of LERU.[22]

Several universities have supported the Gold route for Open Access, whereby authors in these institutions either publish in Open Access journals or pay publication charges (funded by the research funder or from an institutional Open Access fund) to make their article available in Open Access on publication. Some research funders, such as the Wellcome Trust in the UK, the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) and the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), will fund such publication payments. The Gold route is a bold route, which may also change the pattern of publication.

In the wake of publishing the Roadmap, some LERU members have become more interested in Gold Open Access publishing. A meeting of interested parties took place in April 2011 in Oxford where a wide range of issues was discussed. A follow-up meeting of LERU Chief Information Officers took place in UCL in London in November 2011. One of the action lines which the meeting agreed was to form a LERU Working Group to look in greater detail at Gold Open Access. In particular, the meeting was interested in investigating further the possibilities for shared Gold Open Access infrastructure across LERU Universities.

The Chief Information Officers noted that the OAPEN project[23] has as its objective to develop and implement a sustainable Open Access publication model for academic books in the Humanities and Social Sciences. The OAPEN Library aims to improve the visibility and usability of high quality academic research by aggregating peer reviewed Open Access publications from across Europe. The meeting of November 2011 also discussed in detail a library consortium business model from Dr. Frances Pinter, which aims to create a new business model for Arts and Humanities monograph publishing.[24] The LERU Working Group will also consider this Business Model in more detail to see whether they can adopt such a model to further the Gold Open Access agenda.

Copyright Reform

In a digital environment, one of the frameworks in which libraries, researchers and teachers have to work is copyright. Copyright legislation, at the Member State or at the EU level, is the framework in which people act. In the UK, the new Coalition Government sponsored a review of the UK’s copyright framework by Professor Ian Hargreaves.[25] One of the drivers for the review was to see whether the UK’s Intellectual Property framework needed to change in the interests of innovation and growth. The answer proposed by the review is that it does.

In relation to personal copying, the Report has this to say:

‘Copying should be lawful where it is for private purposes, or does not damage the underlying aims of copyright...

‘The UK has chosen not to exercise all of its rights under EU law to permit individuals to shift the format of a piece of music or video for personal use and to make use of copyright material in parody. Nor does the UK allow its great libraries to archive all digital copyright material, with the result that much of it is rotting away. Taking advantage of these EU sanctioned exceptions will bring important cultural as well as economic benefits to the UK. Together, they will help to make copyright law better understood and more acceptable to the public. In addition, there should be a change in rules to enable scientific and other researchers to use modern text and data mining techniques, which copyright prohibits.’

The review had similar strong things to say about Orphan Works.

‘It [the UK Government] should begin by legislating to release for use the vast treasure trove of copyright works which are effectively unavailable — “orphan works” — to which access is in practice barred because the copyright holder cannot be traced. This is a move with no economic downside.’

The Report suggests that, if all its recommendations are adopted, the result will be stronger rates of innovation and increased economic growth. An economic impact assessment conducted by the review team, and of course subject to the high degree of uncertainty inherent in such projections, estimates that this would add between 0.3 per cent and 0.6 per cent to annual GDP (Gross Domestic Product) growth. The path laid down in this review would also, over time, mean that intellectual property law, including copyright law, would become clearer and be observed by most people without controversy.[26]

Spurred on by developments such as the Hargreaves review, European research and national libraries have begun to lobby for copyright reform across Europe. 2011 saw the creation, with private sponsorship, of Information Sans Frontières (ISF).[27] Amongst its members are the JISC (Joint Information Systems Committee) in the UK, LIBER, Europeana, and EBLIDA. IFLA is an observer on the Steering Committee. ISF was formally constituted in September 2011. It has two advocacy officers, based in the UK and Brussels, who work with the EU institutions to put the case for academic-friendly copyright reforms across Europe. The first work of the ISF is on the European Commission’s Proposal for a Directive on certain permitted uses of orphan works with a view to establishing common rules on the digitisation and online display of so-called orphan works. The ISF has laid down reasons why it believes that the draft Directive should be re-cast. Time will tell whether they are successful.

Conclusions

What conclusions can be drawn from this overview of European library activity in a time of economic crisis? Joint procurement can deliver savings through bringing a large number of libraries to the negotiating table together. In this way, it is possible to do more with the level of resource that is available. Innovation through collaboration and shared services is certainly a fruitful area for future growth. The DART-Europe portal provides access to 250,000 research theses and is a successful collaboration amongst several hundred European universities. RLUK is beginning to look at new models of deep sharing, based in the cloud, for collaborative cataloguing which could deliver savings to members and avoid much of the waste and duplication that is inherent in the present system. There are new sources of income available to European research libraries, but for many libraries this is a new development and would need to become embedded into their organisational structures. Finally, the paper shows that growth and development can come from changes to legal frameworks, and looks to the Hargreaves review in the UK and the new work of Information Sans Frontières (ISF) for indications of what is possible.

Notes

|

For this and what follows, see L. Estelle, ‘Big Deals and Alternative Business Models’, delivered at the 2011 annual meeting of the Chief Information Officers in LERU Universities (League of European Research Universities) at http://www.leru.org/index.php/public/extra/cio-28112011/. |

|

|

The Report can be found at http://ec.europa.eu/research/science-society/document_library/pdf_06/open-access-report-2011_en.pdf |

|

|

See Hill, R. and Moyle, M. (2010), ‘Investigating the Impact of e-Theses at DCU’, Presentation at the 2010 LIBER Annual General Conference, http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/19955. |

|

|

Available on YouTube at www.youtube.com/watch?v=GIU14-3hYto. |

|

|

See http://www.ucl.ac.uk/news/staff/staff-news/05122011-mbrowne?dm_i=UAA,NDYU,3YRLM9,1W32P,1, where Michael Browne (Head of UCL’s European Research and Development Office) analyses the importance of European funding for universities. |

|

|

For further information on LIBER’s EU project portfolio, see P. Ayris, ‘Establishing the Library Landscape in Europe: LIBER’s Portfolio of EU projects’ in LIBER Quarterly, vol. 21 2011 (1). |

|

|

The Roadmap is available at http://www.leru.org/files/publications/LERU_AP8_Open_Access.pdf |

|

|

All the quotations in this section are taken from the Executive Summary, pp. 3–9. |

|