The Role of the National and University Library of Slovenia in a Multinational Research Project (IMPACT): a Case Study

Abstract

In this paper, the participation and the role of individual libraries acting as partners in research project consortia, dealing with digitisation issues are analysed, following the example of the National and University Library of Slovenia (NUK) as a partner in the IMPACT project — Improving Access to Text. IMPACT is funded under the Seventh Framework Programme of the European Commission (FP7) aimed at improving automated text recognition of digitised materials from different European digital collections. To achieve the project’s objectives, a consortium of partners comprised of several European libraries, information technology and software engineering centres, and linguistic institutes was established. The consortium’s work was based on interdisciplinary collaboration in which libraries (like NUK) played an important role firstly as demonstrators of tools and procedures developed within the project, and secondly as representatives of end-users’ needs and demands.

Different European digitisation projects in the past have already included national libraries as project partners and the results of collaboration have been so far quite positive. A case study methodology is used for exploring several dimensions of such collaboration. First of all, the study shows that the consortium ensures libraries the economic and expert groundwork needed for the effective realization of the objectives outlined in the framework of the project. Secondly, the study shows positive results when comparing the sum total of knowledge and experience gained over the course of the project and the efforts invested in it by individual libraries. On the basis of such a success, NUK will be able to expand its digitisation plans. Other advantages include more concrete project outcomes, such as the formation of a common multinational digital collection, applicable OCR technology and metadata standardisation. A comparative study with some of NUK’s other on-going projects shows differences and similarities in the library’s collaboration in applicative and research project schemes. Furthermore, the main results of the library as a demonstrator in the project are presented — they are in accordance with the library’s strategic goals and its official role in the information society.

Thus, this case study may be considered as an example of a best practice for participation of a national library in interdisciplinary research projects. It also shows, that national libraries can be important and active partners not only in an applicative, but also in scientific research project consortia.

Key Words: IMPACT project; research project; national library; case study; digitisation; OCR; best practice

Introduction: Defining the Subject of the Research and Methods Used

In this case study, the main research focus on the question whether or not participation of the National and University Library of Slovenia (NUK) in the IMPACT project is beneficial to the institution. To arrive at an objective conclusion, a short overview is provided of the IMPACT project and of NUK’s activities and its users. The key national documents on which the strategy is based are shortly presented. In addition, a comparison is drawn with NUK’s other on-going projects within different EU funding schemes. The comparison includes project finance models and results. In particular, the projects DRIVER II, Europeana and eBooks on Demand (EOD) will be compared with the IMPACT 2[1] project. By inductive reasoning we will be able to draw general conclusions and answer two more universal questions:

-

Is participation of national libraries in international research projects beneficial to the partner institutions, and if so, why?

and

-

Could issues arising from mass digitisation be solved at an institutional/national level, or is collaboration at an international level needed to resolve them?

The IMPACT Project Framework

In the last decade the European Union (EU) has paid special attention to the preservation, development of the digital cultural heritage and user-focused presentation of European historical resources. For this reason the EU has published a number of resolutions, strategies and recommendations which will stimulate research and development in the field of digitisation, digital processing and promotion of our common European identity and the identity of individual nations.

The EU’s i2010 Strategy, which was published in 2009, formed the basis for the IMPACT project. The project is funded under the Seventh Framework Programme of the European Commission (FP7). The aim of the project is to improve access to historical texts that were digitised in European mass digitisation initiatives by furthering innovation in automated text recognition and by developing new tools and applications for Optical Character Recognition (OCR) of printed materials published between the start of the Gutenberg era (15th century) and the emergence of industrial book production in the middle of the 19th century. The four-year project is coordinated by the Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Netherlands, and was launched on 1st January 2008. It was divided into four subprojects (Operational Context, Text Recognition, Enhancement & Enrichment, and Capacity Building) and was carried out in two phases. The first phase lasted for two years and included 15 institutions (7 libraries, 6 research institutes and universities, and 2 commercial companies). Early in 2010 the National and University Library of Slovenia (NUK) joined the project consortium as a second phase demonstrator.[2] Presently 26 institutions from 13 EU countries are involved in the project (12 libraries[3], 12 research institutes and universities[4] and 2 commercial companies[5]).

Each project partner has its own specialisation; together they constitute an interdisciplinary group which is very conducive to sharing expertise and developing best practices as well as capacity in digitisation across Europe. In addition, the project includes the establishment of a Centre of Competence (CoC) in order to provide a central service entry point for all institutions and individuals involved in the digitisation of textual material.

The purpose of the project is first of all to improve access to historical texts by providing quality OCR results. This will be achieved through development of new OCR tools and additional supporting applications to already existing tools. The supporting applications will include lexicons for historical languages which might be integrated into the OCR tools, or be used as independent tools.

Secondly, the project will provide and disseminate best practice solutions for mass digitisation of European cultural heritage in the European Union and beyond: the project will assess already established national and international standards related to digitisation procedures and will establish its own body of collective standards.

The third purpose of the project is the establishment of the aforementioned Centre of Competence, which will ensure international availability of the newly developed tools and which will act as a centre for help, support and education in digitisation matters at the international level.

In particular, the project focuses on finding solutions for errors and imperfections that occur when texts are OCR processed by today’s state-of-the-art tools. There are three types of errors:

-

errors originating from language characteristics

-

errors originating from print properties

-

errors originating from digitisation procedures.

To resolve these issues, linguists from the project are building the historical lexicons which take into account, e.g., historical alphabets, vocabularies and special characters and which enable digital library users to search in historical texts with modern words. In addition, the software developers have developed 22 new applications for pre- and post-processing of digitised pages (scans), which can automatically detect segmentation, remove noise, ignore different fonts and type sizes, etc.[6]

The Role of Libraries in the Project

In the project some of the largest national and university libraries of Europe are working together. They represent end-users’ needs and demands which were instrumental in defining the project objectives and which were in fact the very reason for the project from the very beginning. Therefore, libraries play an important role in the project. Specific library tasks are:

-

project management, coordination and networking

-

provision of material for research

-

demonstration, evaluation and testing of project results (programs)

-

dissemination activities.

The first responsibility of libraries was, of course, content provision, that is why libraries were called Content providers. The availability of material for research purposes allowed the development of software within the project. Besides this, libraries also organised the production of a primary research corpus of texts in their own institution or with the help of third-party companies. This was called the production of Ground Truthing (GT). For the GT, all the libraries made a selection of a representative content from the material selected for the IMPACT project.[7] The selected texts went through a several step process. First of all, state of the art OCR programs produced a rough copy which was then edited by hand to an accuracy rate of almost 100%. After that, the results were reviewed and quality control was applied.

But libraries can do much more than merely provide content. Some libraries which participated in the IMPACT project from the very beginning were leaders of the project work packages. Libraries such as NUK (second phase demonstrators), on the other hand, were mainly responsible for delivering on some of the project tasks, while working within their individual project plans.

Libraries also provided useful information on the problems they have encountered in mass digitisation processes. This information was later used to develop pertinent and effective software, which was helpful at usability analyses of the tools. Such information also included end-users’ needs and demands. For example, NUK represented different groups of digital library end-users from the Slavic-speaking language region.

Another important responsibility that all IMPACT project partners shared, but especially libraries as individual entities, was networking and establishing a network of digitisation specialists. Events were also organised to disseminate the project’s results.

NUK — a Library in the Modern Information Society

NUK, the national and university library of Slovenia,[8] serves more than 200,000 on-site visitors per year and more than 1 million distant users,[9] who mostly access digital resources from our portal of information resources (international and national journals and other online databases) and digitised documents from our Digital Library of Slovenia (dLib.si). dLib.si was established to provide the broadest access possible to library materials and to support modern library and information science development.

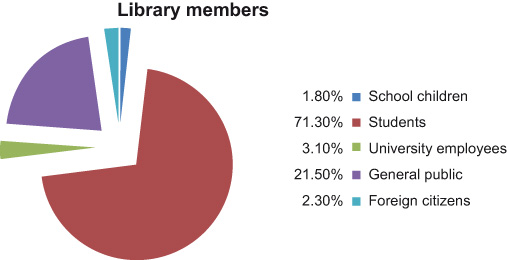

NUK’s users include school children, students, university staff, the general public (other adults) and foreign citizens (see Figure 1). As such, NUK’s user community is quite representative of the modern library user who requires access to printed resources but also to digital resources (born-digital documents and digitised books, newspapers, manuscripts, pictures, maps, typewritten documents, etc.) that can be accessed from their home, office, school and can be viewed on different devices (computers, ipads, phones, etc.).

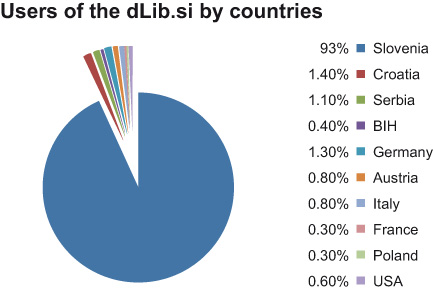

The target groups of users who access digital resources from the dLib.si do not differ from the target group that visits the library in person. Mostly they are students, researchers and other university staff, school children, and the professional and general public.[11] With the help of Google Analytics, which registers only searches made by actual users and ignores searches by web indexing robots, we measured more than 2.8 million visits to the dLib.si portal. The users of the portal were mostly from Slovenia, but also from other European countries and even from the United States of America (see Figure 2).

Digital collections are built and included in the dLib.si in response to users’ needs and in accordance with Slovene regulations, standards and national digitisation policies.[13] Moreover, collection development is guided by the strategic goals of NUK for 2010–2013. Material is selected and digitised on the basis of NUK’s remit to preserve, protect and conserve the national written cultural and scientific heritage. In addition, special attention is paid to building, maintaining and providing access to digital collections of national importance and to expanding digital scientific and research collections. These two strategic goals are correlated with the main task the library has as the national library: to consistently and comprehensively collect the nation’s published output, called Slovenica, in all formats, and to process acquired material effectively and immediately, giving users free and easily accessible content.

In June 2011 dLib.si contained more than 4 million scans of documents that are no longer under copyright or can be made available with the author’s permission. Digitised Slovene historical documents, which are included in the digital collections on dLib.si, have a large number of spelling variants, similar to printed materials from other EU countries included in the IMPACT project.[14] Spelling variants together with changeable font sizes and other errors already mentioned above interfere with the OCR process, which fails to produce satisfactory results.

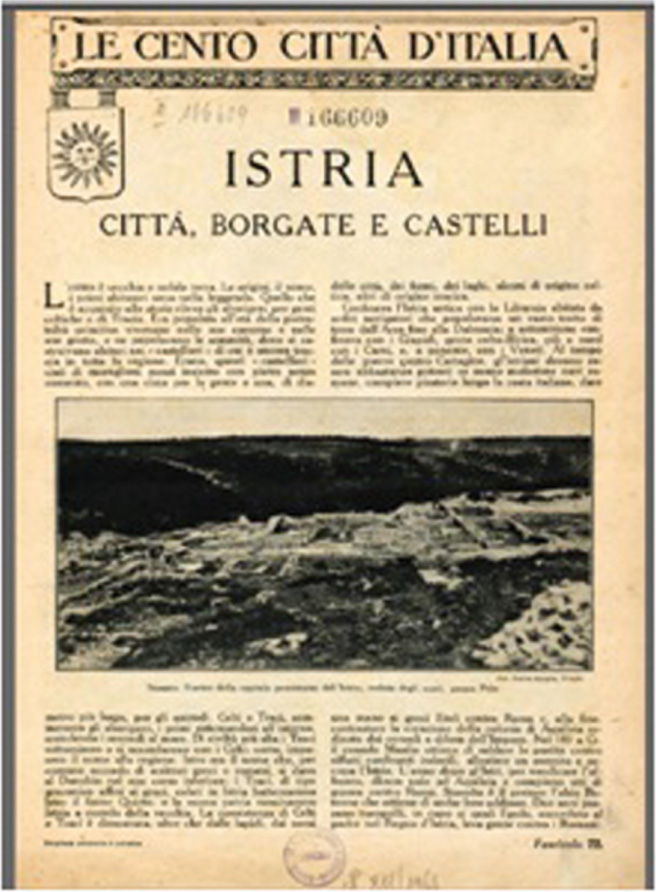

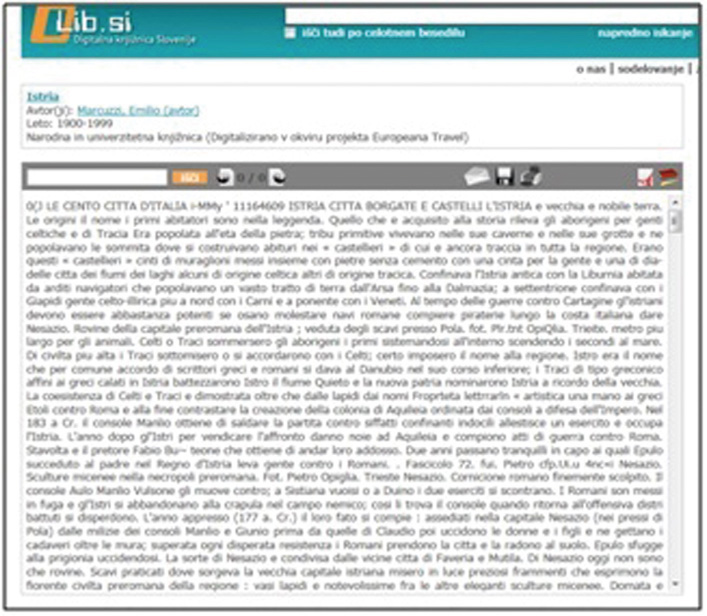

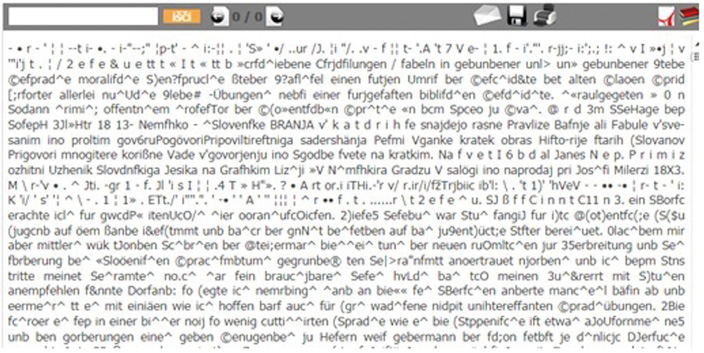

Users of the dLib.si normally use web search engines and full-text search options to look for specific historical texts they need for their studies or other purposes. They have difficulties finding the desired materials when errors affect the OCR results, because the full text search is disabled. Statistics for dLib.si content access in the first four months of 2011 have shown that the HTML preview and PDF files are equally used (both scoring 49%),[15] although the HTML version is much harder to follow (see Figures 3 and 4), as the preview opens in an internet window with no page segmentation. Although headings, paragraphs, page numbers etc. are difficult to recognize, the text can be copied, modified and reused further on. PDF files, on the other hand, can be downloaded and saved on a local computer. The PDF gives the viewer an exact duplicate of the scanned document.

In documents published before 1850 (or sometimes even after this date), a very archaic type of Slovene was used.[16] OCR results of these documents are very poor indeed and the HTML previews are not only an unrecognizable mass of letters but contain numerous errors and strange signs, numbers instead of letters, spelling mistakes etc (see Figure 5). In such cases full-text search is disabled and further usage of the text is impossible.

For NUK as well as for other libraries it is very important that the problems that users have are adequately addressed, solved, and eliminated. These problems tend to be complex and multifaceted and appropriate solutions may only be found in collaboration between specialists working in different fields. Such cooperation is customary in EU projects. Some of the issues arising from NUK’s digitisation practices were already addressed in other EU projects in which NUK was or is a partner. The next section will compare the IMPACT project with other projects dealing with digitisation issues, showing us the strengths and weaknesses of such collaboration.

NUK in Other European Projects

NUK has been participating in projects co-financed by the EU Commission from 2001 on.[17] Especially since 2004, when the EC work programmes started supporting activities related to digital library development, NUK was given the opportunity to establish very good international expert networks in different projects (Kavčič-Čolić, 2010).[18]

Similarly to the IMPACT project, the DRIVER II project in which NUK took part was co-financed by the 7th Framework Programme of the EU,[19] which means the funding model was the same (75% co-financed from the EU for research activities and 50% for demonstration). The work in both projects was done by libraries and universities with technical development partners, and in both cases a network was established for sharing knowledge and expertise.

Unlike the IMPACT network, the DRIVER II network was an open network, which allowed new members (such as research and academic organizations) to join the network through established infrastructure nodes in individual countries. The result was a service which could be extended to any given region (Kavčič-Čolić, 2010). It resulted in the Confederation of Open Access Repositories (COAR) which consists of members from the entire world. The IMPACT project network was only extended once after the first project phase ended. The new IMPACT Centre of Competence (CoC) for digitisation, which was officially launched at the final IMPACT conference (24th to 25th October 2011, London),[20] will allow the established IMPACT project network to continue operating. Also, new members will be able to join the network through one common access point.

Besides the 7th Framework Programme of the EU, an interesting EC co- financing scheme was eContentPlus, which expired in December 2008. It was continued under the CIP ICT PSP programme. These two EC programmes supported (for 50%) the development of the European Digital Library/Europeana and some of its subprojects such as Europeana Travel and Europeana Local. NUK participates in all three of them.

Europeana operates as an open network, encouraging new members to join and share their contents. Its network increases also through new EU projects which are supported and promoted every year by the EC, to push the development of the common EU digital library even more. Europeana’s network is divided into separate regional, national or local content-gathering contact points. NUK is one of the national aggregators for Europeana and as such it is also the contact point for Slovene content providers.[21] NUK’s participation in Europeana brought NUK the standardisation models used in the Europeana network. These standards were used in the development of metadata for dLib.si. In this way the metadata of all digital objects entered into dLib.si correspond to international regulations and are of high quality. When preparing the material for the IMPACT project we had no difficulties with the scans which were made according to these standards, whereas earlier scans were of significantly poorer quality, causing us problems in the preparation of the corpus. They required extra work before they could be included.

Another EC funding scheme in the field of cultural heritage is the Culture Programme 2007–2013. It gives financial support (50%) to the on-going project EOD — eBooks on Demand, one of the services NUK offers to its end-users. The EOD network is a growing network of European libraries and archives[22] which enables the active participation of end-users in digitisation planning in libraries. The EOD project provides very good feedback on what library end-users want, especially in identifying which material is most important to them. The project enables NUK to set digitisation priorities lists and focus on the most desired material.

There is an interesting correlation between the EOD and IMPACT projects. When staff working on EOD prepares a book ordered by an end-user, they use existing tools to improve the digital images. Digitised books can be sent to the user in printed form (as a kind of facsimile) or in PDF format with attached OCR. The staff does not correct the OCR manually for the whole book,[23] but leaves it as it is. Although the staff in the two projects uses different tools now readily available on the market, they deal with the same issues the IMPACT project is trying to resolve.

International Project Participation: Benefits and Challenges

Benefits

As the usability of the texts and full-text search in the documents are crucial features for our digital library users, it was imperative that NUK starts participating in the international IMPACT project. Tools and applications delivered by the project will help NUK to provide better digital resources to its users. Twenty-two software applications were developed to eliminate OCR errors. These were created in collaboration between software developers, library digitisation specialists and language researchers and they could never have been produced in-house.

By participating in the IMPACT project, NUK was able to make a significant contribution to the implementation of national strategic goals for the development of the Slovene information society — mostly (but not limited to) by assuring all users good-quality, state-of-the-art internet support and widely accessible resources and services which are in the public interest (Strategija, 2006, p. 26–40).

By summarising NUK‘s experiences in the past years of collaboration in the projects mentioned above and by comparing different working practices we can identify the following positive effects:[24]

New knowledge and best practice solutions. Projects enable libraries to transform merely theoretical knowledge into real practical implementation. For example, in DRIVER II NUK became practically acquainted with new metadata and content interchange protocols.[25] In the IMPACT project NUK gained even more practical knowledge in digitisation and by taking over and incorporating a task of preparing a primary corpus of texts for research,[26] which is work normally outsourced to private companies.[27] NUK gained indispensable experience in the practical execution of work that would otherwise have been very expensive. In doing this, NUK also had to work closely with the science Institute ‘Jožef Stefan’, which resulted in important and effective collaboration.[28]

Collaborative work in developing international standards is also very important for individual institutions, which first get to contribute their own experiences and then they are allowed to learn and adopt best practice solutions as well as develop interoperability. For example, in Europeana and EOD NUK participated in the creation and implementation of digitisation standards (Kavčič-Čolić, 2010). Adoption of these standards is often a precondition for participation in new projects.

All in all, the knowledge gained during the projects supports innovation in library work in-house and elsewhere in Slovenia.

Cooperation and integration in international networks. Integration into broader international communities enables NUK to develop broader and more objective approaches to digitisation problems. For example, in the EOD project two new services were developed: digitisation and printing on demand (Brumen and Svoljšak, 2009), which at least partially help in providing end-users with the useful materials they need and want.

Project work is usually divided into work packages and the work is distributed between project members. Staff involvement and team work are very important for successful delivery of the project results, as NUK has learned from the IMPACT project, where specialists from different disciplines were involved. The working group really had to work together to fulfil its mission.

By joining international research networks researchers and institutions such as NUK feel like they belong to the international professional community (Kavčič-Čolić, 2010), which is extremely important for small nations like Slovenia.

Cooperation at the national level has already been mentioned above. Through the IMPACT project many connections were established between universities, libraries and research institutions.

Additional resources and financial support. Last but not least, cooperation in EU projects provides libraries with additional funding to develop their services and collections. The knowledge acquired can be shared with new professionals, additional equipment can be purchased and new software licences bought (Kavčič-Čolić, 2010).

Challenges

In addition to positive effects, projects also represent some challenges for partner institutions. Based on the above-mentioned projects we can identify:

Sustainability issues. Most problems connected with sustainability are related to the implementation of the project results and continuing employment of the project staff after the project ends. These two issues are closely correlated — if there is no funding to retain the project staff, the knowledge and practical project experiences are lost.

Funding difficulties. The problem of sustainability is closely related to the next project challenge, which is ensuring sufficient funding for the realisation of the project. As mentioned above, funding schemes vary in the percentages of co-funding by the EC. Assets are dedicated and limited. Sometimes the institution has difficulties predicting in advance how much time and manpower will be needed for completion of one task and what other expenses may arise during the project, especially if the project is multi-annual.

Conclusion

Throughout the text we have shown how important it is not only for NUK to participate in IMPACT, but also, more generally, for individual institutions to cooperate in multinational research projects. The benefits of project collaboration are far greater than the possible risks and difficulties.

With the IMPACT project NUK developed much-needed knowledge to overcome its own problems arising from digitisation. NUK will also accumulate this knowledge and bring it to bear on similar issues at the national level. NUK will be able to properly present the newly formed Centre of Competence for digitisation to its business partners and other interested parties from the professional public.

As a national library, NUK has a special responsibility towards Slovenians (its end-users) to protect nationally important (printed and digital) sources and to provide free and easy access to these resources. As university library its emphasis is more on providing excellent services and digital resources. Participation in international projects like the IMPACT contributes to reaching these important objectives.

More specifically, by collaborating in the IMPACT project more than 5,000 digitised pages written in historical Slovene from the time when the modern Slovenian language was formed (from the second half of the 18th to the first half of the 19th century) were manually reviewed and corrected. Almost 100% accuracy provides the library end-users with important easily accessible and searchable contents. The second result of the project was a lexicon of historical Slovene, which will be integrated into the digital library dLib.si after the project and which will enable end-users full-text searches with modern words in more than 200,000 digitised documents written in historical Slovene.

Collaboration within the IMPACT project and other projects dealing with digitisation also showed that issues arising from mass digitisation can be better solved at the international level. These projects combine national practices and standards to form common project guidelines that often result in universally acceptable standards. Also best practice solutions can contribute to finding effective solutions.[29]

Large projects like IMPACT also further establishing of new connections which foster further collaboration between individual institutions in international networks.

Furthermore, the consortium ensures libraries the economic and expert groundwork for the effective realisation of the objectives outlined in the framework of the project. The consortium also yields positive results when comparing the experiences achieved within the project with the efforts invested by individual libraries.

References

|

Brumen, M. and S. Svoljšak (2009): ‘EOD — po treh letih uspešnega delovanja nadaljujemo z novim projektom’, Knjižničarske novice, 19(9), 29.

|

|

Erjavec, T., I. Jerele and M. Kodrič (2011): ‘Izdelava korpusa starejših slovenskih besedil v okviru projekta IMPACT’, Simpozij obdobja 30: meddisciplinarnost v slovenistiki (17–19 November 2011, Ljubljana, Slovenia). Also available at http://www.centerslo.net/l1.asp?L1_ID=4&LANG=slo..

|

|

Gotscharek, A., A. Neumann, U. Reffle, C. Ringlstetter and K.U. Schulz (2009): ‘Enabling Information Retrieval on Historical

Document Collections — the Role of Matching Procedures and Special Lexica’. AND2009 Workshop (23–24 July 2009, Barcelona, Spain). Also available at http://sites.google.com/site/and2009workshop/.

|

|

Jerele, I., T. Erjavec, D. Pokorn and A. Kavčič-Čolić (2011): ‘Optical Character Recognition of Historical Texts: End-User

Focused Research for Slovenian Books and Newspapers from the 18th and 19th Century’. In: 6. SEEDI Conference: Proceedings (16–20 May 2011, Zagreb, Croatia), p. 11 (as yet unpublished). Also available at http://www.nsk.hr/seedi/seedi-hrv/index.html.

|

|

Kavčič-Čolić, A. (2010): ‘Achieving Library Development through European Projects: the Case of the National and University

Library of Slovenia’. In: Zbornik radova 10. okruglog stola o slobodnom pristupu informacijama: Utjecaj globalne ekonomske krize na knjižnice i slobodan pristup informacijama (10 December 2010, Zagreb, Croatia). Also available at http://www.hkdrustvo.hr/hr/skupovi/skup/179.

|

|

Krstulović, Z. and M. Kragelj (2011): ‘Nacionalni agregator e-vsebin s področja kulture’. In: Nove razmere in priložnosti v informatiki kot posledica družbenih sprememb: zbornik konference. Also available at http://www.dsi2011.si/..

|

|

Letno poroćilo 2010 (2011): Ljubljana: Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica.

|

|

Line, B. (2001): ‘Changing perspectives on National Libraries: A personal view’, Alexandria, 13(1), 43–49.

|

|

National and University Library of Slovenia Short Annual Report for 2009 (2010): Ljubljana: Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica..

|

|

Slovenska nacionalna knjižnica: ob 60-letnici preimenovanja v Narodno in univerzitetno knjižnico (2006): Ljubljana: Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica.

|

|

Stake, R.E. (1995): The art of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

|

|

Strategija razvoja digitalne knjižnice Slovenije dLib.si 2007–2010 (2006): Internal document.

|

|

Strategija razvoja informacijske družbe v Republiki Sloveniji: si2010 (2007): Ljubljana: Vlada Republike Slovenije.

|

|

Svoljšak, S. and J. Klasinc (2010): ‘Vzpostavljanje storitve EOD — ‘e-knjige po naročilu’ v NUK: pregled opravljenega dela

po dveh letih delovanja storitve’,

Knjižnica: revija za področje bibliotekarstva in informacijske znanosti = Library: journal for library and information science, 54(1/2), 137–155.

|

|

Štular Sotošek, K. (2009): ‘Digitalna knjižnica Slovenije — dLib.si in sorodni multimedijski portali = The Digital Library

of Slovenia — dLib.si and related multimedia portals’, Šolska knjižnica, 19(2/3), 118–125.

|

|

Štular Sotošek, K. (2011): Best practice examples in library digitization. Ljubljana: Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica. Also available at http://dlib.si/details/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-BBNAEBQJ.

|

|

Yin, R.K. (2009): Case study research: Design and methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

|

Notes

|

When the IMPACT project was expanded to include more languages, the project entered the second phase of realization. At this point the official name of the project was changed to IMPACT 2. But since IMPACT and IMPACT 2 are one and the same project, we will only use the short version of the acronym here (without the number). |

|

|

All the libraries in the consortium are so-called demonstrators. The ones participating in the project from its beginning are the first phase demonstrators; the ones that are on board since 2010 are so-called second phase demonstrators. The term derives from ‘demonstrating the tools’, one of the responsibilities libraries have in the project. |

|

|

The libraries are: Koninklijke Bibliotheek (Netherlands), The British Library (United Kingdom), Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (Austria), Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (Germany), Bayerische Staatsbibliothek (Germany), Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen (Germany), Bibliothèque Nationale de France (France), ‘St. Cyril and Methodius’ National Library (Bulgaria), Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica Slovenije (Slovenia), Národní knihovna Ceské republiky (Czech Republic), Biblioteca Nacional de España (Spain), Uniwersytet Warszawski (Poland). |

|

|

These are: Universität Innsbruck (Austria), Instituut voor Nederlandse Lexicologie (Netherlands), National Centre for Scientific Research ‘Demokritos’ (Greece), Centrum für Informations- und Sprachverarbeitung, University of Munich (Germany), University of Bath and University of Salford (United Kingdom), Bulgarian Academy of Sciences (Bulgaria), Jožef Stefan Institute (Slovenia), Institute of the Czech National Corpus and Charles University Prague (Czech Republic), ATILF-CNRS & University of Nancy (France), Fundación Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes and Universidad de Alicante (Spain), Poznan Supercomputing and Networking Center, Uniwersytet Warszaws (Poland); see http://www.impact-project.eu/about-the-project/partner-information/. |

|

|

These are: ABBYY Production (Russia) and IBM Israel — Science and Technology Ltd. (Israel). |

|

|

Some of the tools are described at http://www.impact-project.eu/taa/tech/tools/ |

|

|

Approximately 5,000 digitised pages. |

|

|

More about the history and establishment of NUK can be read at: http://www.nuk.uni-lj.si/nukeng1.asp?id=123006838. |

|

|

The number was taken from research published in the monograph Slovenska nacionalna knjižnica (2006, p. 10). |

|

|

The data were taken from NUK’s 2010 annual report and show that most of our users are students and the general public (2011, p. 41). |

|

|

dLib.si concentrates on these groups of users from the beginning (ibid, p. 75). The statistics on access to dLib.si in 2010 show a 73% increase compared to 2009 (ibid, p. 77). |

|

|

Ibid (p. 78). |

|

|

See Slovene national strategies on digitisation and cultural heritage preservation: Strategija razvoja informacijske družbe v Republiki Sloveniji si2010 (the Government of the RS, 2007) and Nacionalni program za kulturo 2008–2011 (Ministry of Culture, 2008). |

|

|

The statistics were published in a paper presented at the 6. SEEDI conference, Zagreb, Croatia, 16th–20th May 2011 (p. 2). |

|

|

Slovene works published between 1550 and 1850 were written in the Bohoričica alphabet. This alphabet included special signs, digraphs and ligatures. In the middle of the 19th century a new alphabet was introduced: Gajica. |

|

|

In 2001 NUK started cooperating with the European Community in the projects TEL — The European Library (see http://search.theeuropeanlibrary.org/portal/en/index.html) and LEAF — Linking and Exploring Authority Files (a description at http://www.ist-world.org/ProjectDetails.aspx?ProjectId=83df3c89ab9f4af89b6d8a6fe68c870a&SourceDatabaseId=9cd97ac2e51045e39c2ad6b86dce1ac2). |

|

|

In the year 2004 Slovenia also became a Member State of the EU, which resulted in many advantages in terms of project participation, since the EC stimulated proposals that focused on integration of new Member States (Kavčič-Čolić, 2010). |

|

|

Ibid. |

|

|

The programme of the conference is available at http://www.impact-project.eu/news/ic2011/. |

|

|

For further information see Štular-Sotošek (2009) and Krstulović and Kragelj (2011). |

|

|

More about the EOD service in NUK in Brumen and Svoljšak (2009) and Svoljšak and Klasinc (2010). |

|

|

Within EOD, only title pages are reviewed and OCR corrected if needed (information from a lecture on new developments in OCR technology OCR — Kaj je to?, Ljubljana, 10th June, 2011). |

|

|

Positive and negative experiences are listed in Kavčič-Čolić (2010). |

|

|

OAI-PMH is an Open Archive Protocol for Metadata Harvesting. Further information can be retrieved from http://www.openarchives.org/pmh/. |

|

|

Lexicon and software development within IMPACT required the best possible basis — a selection of texts with almost 100% OCR result (i.e., 99.95%) not only at the word level but also at the level of individual characters, with equally well recognized page segmentation. The project policy was that every project partner should select at least 30,000 digitised pages, which were included in a joint project database of scans of historical texts in different European languages. See http://www.prima.cse.salford.ac.uk:8080/impact-dataset/index.php. From single language collections provided by one project partner a smaller selection was designated for research. NUK provided altogether 40,000 scans, of which 5,000 representative scans were manually corrected to 99.95% accuracy. |

|

|

Often highly priced private companies are employed in scanning library material and producing OCR for texts. Sometimes they are asked to provide manual corrections of the OCR to get better results. Because of the language specifics of archaic Slovene and bad OCR results, no private company was willing to produce the aforementioned corpus for NUK. NUK decided to produce it in-house and recruit language and digitisation specialists. |

|

|

The ’Jožef Stefan’ Institute is a linguistic partner in the IMPACT responsible for development of a lexicon for historical Slovene. |

|

|

For further reading see Štular Sotošek (2011). |