e-Readers in an Academic Setting

In this paper the authors will discuss a pilot project conducted at the Tritonia Academic Library, Vaasa, in Finland, from September 2010 until May 2011. The project was designed to investigate the application of e-readers in academic settings and to learn how teachers and students experience the use of e-readers in academic education. Four groups of students and one group of teachers used Kindle readers for varied periods of time in different courses. The course material and the textbooks were downloaded on the e-readers. The feedback from the participants was collected through questionnaires and teacher interviews. The results suggest that the e-reader is a future tool for learning, though some features need to be improved before e-readers can really enable efficient learning and researching.

In the autumn of 2010 The Tritonia Academic Library started an e-reader project with funding allocated by the city of Vaasa, in honour of the city’s 400-year anniversary. In 2010 there was a growing interest in e-readers and tablet computers, especially in the local press, which also spurred the idea to start a project to examine the use of portable reading devices in an academic setting. The purpose was also to gather more knowledge about e-books and e-readers in libraries and to promote the services of Tritonia.

The aim of the project is to investigate the application of e-readers in an academic setting and to learn how teachers and students experience the use of e-readers in academic education.

Tritonia is a joint academic library for five universities: the University of Vaasa, VAMK University of Applied Sciences, Åbo Akademi University, Novia University of Applied Sciences and Hanken School of Economics. Tritonia also provides pedagogical services for the staff of all five universities. Of the 12,000 students, 70% have Finnish as their mother tongue, while the remaining 20% are Swedish-speaking.

The printed collections consisting of 336,000 volumes are available for all students and staff of the five universities and universities of applied sciences, as well as for external library users. By contrast, all electronic resources are licensed for a specific organisation and only the students and staff of the particular organisation have access to those. Because of this, one single e-book may have to be acquired separately for all the five organisations. This is challenging for both the library staff and the library users.

In addition to traditional library services, Tritonia also offers educational support at the EduLab unit. The activities that Edulab is based upon are pedagogical courses (25 ECTS), guidance and media production, which are offered for free to the staff of all five universities. Since the start in 2001, the main goal has been staff development and support.

The e-book and e-reader market is booming at the moment. Amazon already announced that they are selling more Kindle books than print books and Apple’s iPad dominates the tablet computer market (Amazon.com, 19.4.2011). In Europe the e-book market has evolved at a slower pace, mainly because of the lack of content and the high price of e-readers and e-books, but the Kindle’s arrival to Europe has livened up the market.

Libraries have also invested in e-books, have purchased e-book databases, have tried out lending e-readers to customers and set up pilot projects. Even so, despite of their best efforts, the libraries have not really forged their way into the e-book business. However, for the future it is more vital than ever that libraries continue to experiment with different e-book models and e-book and e-reader solutions.

Several studies concentrating on e-books and articles about e-readers were published at the beginning of the 21st century. However, the devices never really broke through until the past couple of years. At the moment more and more studies again focus on e-readers, e.g., Clark et al., (2008) dealt with user experiences and users’ opinions about e-readers in their survey conducted at Texas A & M University Libraries. The participants in the study, members of the library and university staff, found the Kindle reader interesting, but questioned the potential usefulness of the device in research libraries on account of licensing issues, graphic display and cost.

Pattuelli and Rabina (2010), on the other hand, attempted to understand the effects of reading devices on everyday reading practices and also potential applications for library services. They gathered feedback from 20 library and information science students, who had used the devices for one week. The results were mixed; however, the usability issues were outweighed by the device’s portability and readers’ convenience of use anywhere.

Both Clark et al., (2008) and Pattuelli and Rabina (2010) focused mostly on leisure reading. The use of e-readers in an academic setting and the potential application of the e-reader as an educational tool have been much less explored themes ine-reader studies. There are a few exceptions, including pilot studies conducted by seven universities in the USA (Damast, 2010) and Aalto University in Finland (Aaltonen et al., 2010). In both studies the students were given e-readers with course material for a certain period of time. The studies encountered certain usability issues. For example, students felt that the lack of colours and the difficulties in navigation, browsing, bookmarking and taking notes made the devices awkward to use.

The purposes for reading and the methods used can offer a starting point for a discussion of the challenges for e-readers, because the way we read varies with the type of literature we read (see Marshall, 2010, p. 33). For example, reading a fiction novel differs substantially from reading a textbook, as in leisure reading the text usually advances linearly. Reading for study and research purposes involves a lot of browsing, glancing, seeking and re-reading. Annotation and navigation are important ways to interact with the text (Marshall, 2010, pp. 37–36.). In order for e-readers to be considered a real alternative or replacement for paper books and computers, reading devices should be able to support different ways of using the devices.

Today’s reading devices are mainly focused on linear reading or, more specifically, reading for entertainment. Most of the devices on the market have annotation and search functions, but as studies indicate, users often find these functions awkward and slow to use (Aaltonen et al., 2010; Damast, 2010). Also, browsing books is often found difficult. Another possible weakness emphasized in an academic setting is the lack of colours, as pictures, charts and tables are important parts of scientific documents.

The different formats can also create difficulties for students and researchers. e-Books in ePUB format, for example, do not have static page numbers, which makes it very hard to provide precise page numbers for citations. PDFs do not have the same problem, but because the PDF format is not scalable, books and documents in this format may require scrolling and are therefore challenging to read on some e-readers (Ballhaus et al., 2010, p. 3).

The significance of information technology in teaching cannot be underrated as the students are already familiar with information technology both in informal and formal settings. They are part of the Generation Y, the Net Generation, accustomed to navigate in the constant information flow. However, the filtering strategies they use to cope with large quantities of information can often be described as hasty and superficial, which reflects how they regard and use information (Parment, 2008). This generation is also more demanding than the previous one, expecting teachers and librarians to keep up with the new technology.

As Cox (2010) points out, the teacher’s attitudes and beliefs as well as the teacher’s willingness to adopt new teaching methods and practices affect the perceived value of IT in learning. Unfortunately, studies indicate that once their training is finished, teachers rarely see the need to question or change their teaching practices, including those related to the use of IT (Cox, 2010, pp. 16–17) A number of researchers have looked at the influence of new technologies on student achievement and learning processes, but the results are both for and against (Minčić-Obradović, 2011, pp. 174–175). For one thing, the potential change tends to be temporary and superficial and teaching and learning methods are seldom transformed profoundly.

e-Books have the potential of being an efficient and effective educational tool, as the combination of text and multimedia can enhance readers’ understanding of abstract concepts and theories (Ballhaus et al., 2010, p. 13; Collier and Berg, 2011, p. 32; Minčić-Obradović, 2011, p. 161). Features such as customisability of text size, the ability to convert text to audio and a built-in encyclopedia also have benefits in education (Minčić-Obradović, 2011, p. 161). Textbooks read on e-readers enable real-time dialogue and discussion between teachers and students, with options for sharing notes, comments and questions. Many e-readers do not yet have these features, but technical development has been so rapid that no doubt we get to see those in the future.

The project was designed to investigate the application of e-readers in an academic setting and to learn how teachers and students make use of e-readers during courses. The data was mainly collected through questionnaires and interviews. In the next paragraphs, we will discuss the choice of e-reader, preparing the test groups, and the data collection methods.

The main reasons for choosing Amazon’s Kindle reader were: a user-friendly interface, an affordable price, a range of functions such as dictionary and text-to-speech and the possibility to download one e-book onto several devices. The closed environment, the lack of EPUB support and the lack of Finnish or Swedish content were not considered major issues, as the aim of the project was not to concentrate on usability issues or to evaluate the device itself, but to focus on the pedagogical aspect of e-readers in general.

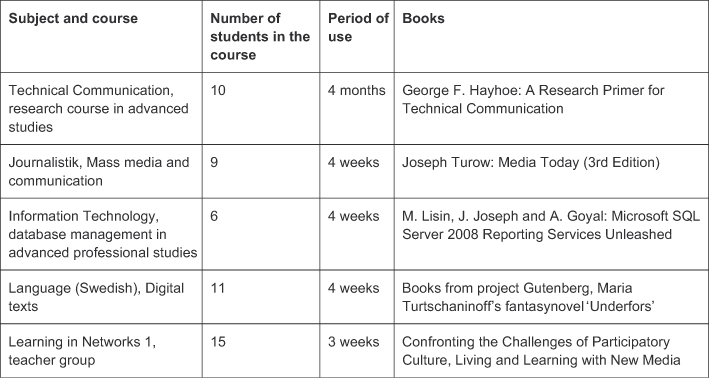

The e-reader project started in September 2010, once the third-generation Kindle became available, and ended in May 2011. During the project five different groups of students experimented with e-readers. The groups are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Test groups.

The groups chosen for the project were small, advanced courses, where the teacher was able to choose the literature used in the course. We approached specific teachers because we knew them to be interested in trying out new methods and techniques. The books and other documents chosen by the teachers were downloaded on 25 Kindle readers (wifi). Later on five additional Kindles were acquired. Kindle DX, Sony PRS-650 reader touch edition, Bokeen Cybook OPUS and iPad I were also acquired, mainly for demonstration purposes.

A short introduction (20–30 minutes) was arranged for the test groups and the students were asked to sign a lending agreement. The participants were also given the possibility to download their own documents on the Kindle reader. The introduction was the only contact with the students and further communication was handled by the teacher.

The students were asked to answer online questionnaires before and after the test period. Due to the project timing and resourcing, the only manageable way of collecting data was through a questionnaire. The questionnaires included open questions as well as multiple choice questions. In the first questionnaire the respondents were asked about their technical skills, studying habits and attitudes towards new technology in general. The second questionnaire related to studying in the course, the use of the device and respondents’ thoughts about e-readers, studying and learning. Three teachers were interviewed to get in-depth insight into students’ reactions and teachers’ thoughts about e-reader applications. We also had access to a blog article and six reviews written by the students as additional assignments in their course.

In addition to the test groups, e-reader and e-book theme days were organised. During these three days over 200 students, staff members and other visitors acquainted themselves with different e-readers and the library’s e-book collections. 67 visitors also filled in a questionnaire, which contained questions about the library’s e-book collections and attitudes towards e-readers.

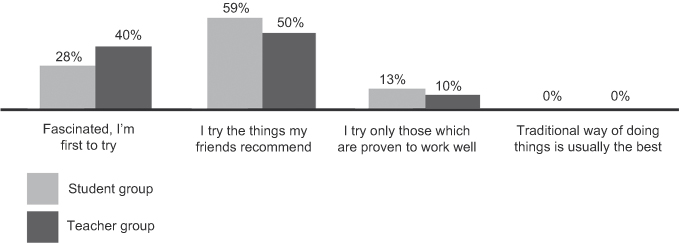

89% of the students filled in the first questionnaire but only 56% (20 of 32) of the students answered the second questionnaire, despite of several reminders sent by email. In the teacher group 10 of 15 teachers filled in the questionnaire. Both the students and the teacher group can be categorised as early adopters or as an early majority on the innovation adoption curve of Rogers (2003, 281), as shown in the graph below. The majority of the respondents estimated their technical skills above average.

In the next sections the respondents’ attitudes towards the Kindle reader and Kindle’s pedagogical value will be discussed.

Figure 2: Respondents’ Attitudes towards the Kindle Reader.

One of the findings of the theme days and the student group meetings was that the e-readers seem to lack the wow-factor, which makes tablet computers like the iPad so attractive. As a couple of respondents pointed out, the lack of colours, basic button navigation and poor internet browsing capabilities made them think of ‘old black-and-white TVs’ and ‘the Middle Ages’. Still, half of the respondents said they would rather read documents on a basic e-reader than on a computer screen.

The teacher group appeared to be slightly more critical towards the Kindle reader than the students, especially judging by the answers to the open questions. In many comments the Kindle reader was compared to the iPad and found to be inadequate, as ‘Kindle cannot compete with iPad, there’s so much more you can do with an iPad’. Even though the students in general gave lower values for different features, they seemed to be more neutral in their attitudes towards the Kindle reader. Many students did not seem to care whether they read the book in paper format or on an e-reader as long as they had access to the book. Based on the students’ comments one may speculate that changing the reading habits and ‘getting used to the different format’, as several students put it, is really a bigger issue for the students than the shortcomings in usability.

The teacher interviews also gave clues about the way the students experienced the use of the e-readers, indicating that for them it would not necessarily be a problem to have a device for one purpose only. The students seem to want to keep their studies and free time apart, and for this reason it is natural for many of them to have different devices for different purposes. That is, the iPad is for ‘all the fun stuff’ like surfing, whereas the Kindle reader is a more serious device, meant for studying and reading. One of the students actually noted that it is a good thing that the Kindle reader doesnot have any unnecessary functions, because it is easier to concentrate on studying.

One of the teachers observed that the students seemed to take the course more seriously and that they were more active and ambitious than usual, but it is impossible to determine if this was a reaction to the new, interesting technology or if there simply were more enthusiastic students in the group than usual.

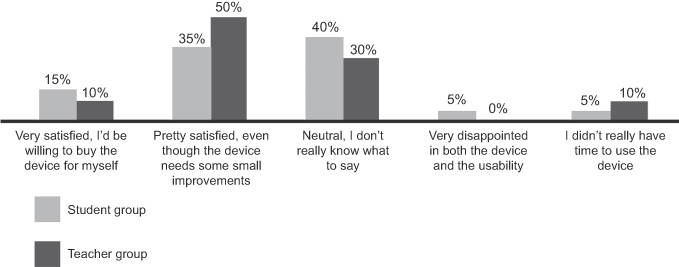

In Figure 3, the overall user experience is shown. Nearly every respondent had a positive or at least a neutral experience with the Kindle reader. A majority of both the teachers and the students also estimated that the effect of the e-reader on studying and learning on the course was neutral or slightly positive.

Figure 3: Overall user experience.

As assumed by previous studies (Aaltonen et al., 2010; Ballhaus et al., 2010; Damast, 2010), the features the respondents missed the most were a touch screen, colours, internet browsing, real page numbers and scandic letters. Many of the teachers were especially dissatisfied with Kindle’s PDF support, as reading the PDF file requires a lot of navigation and the size of the text is small. The most appreciated features were the readability of the text, the portability, and the long battery life of an e-reader.

Only a few respondents had previous experience with e-readers, so they — as was expected — found it difficult to evaluate the potential application of the device in teaching and learning. The students were most pleased that they did not need to chase textbooks in the library and carry heavy book bags to school. The three teacher interviews gave some insight into possible ways of using e-readers.

Teacher 1 found it very important that his students, as future journalists, would read and explore text in the same way as their future readers will explore the text written by the students. The use of the e-reader caused the teacher to rethink his teaching methods and also to present a concrete plan as to how the course could be developed utilising the Kindle reader to enhance the students’ understanding of the subject. He also had ideas about using the Kindle for presenting reports.

Teacher 2 held this course for the first time and therefore did not yet have any ideas for renewing it. The idea of the course was to explore digital texts and the teacher got special permission from the publisher to use a Swedish fantasy novel as course material. The students were satisfied that they could read a book without others knowing what they read and that they could alter the font size. As future primary school teachers, they also speculated whether the e-reader could increase the motivation for reading among boys. These students felt that reading fiction would enhance the experience with multimedia and linking to web pages. Especially the fantasy novel with many references to real places would have given them a better reading experience if they could have used the web while reading.

The third interviewed teacher was not fully convinced of the benefits of e-readers in learning and teaching, mainly because of the difficulties in browsing books and the poor support for PDF files. In her courses books are usually used as reference literature and with the Kindle it was hard to navigate between chapters and get an overview of the book. She also uses lots of PDF articles, which are awkward to read on the Kindle since they require scrolling.

In her opinion, the ideal teaching aid would not be the traditional book, but a service where a selection of different devices would be offered together with digital materials and pedagogical support. Another function she desired was a shared notation system.

Even though the study was a pilot project and the results may not be generalised because of the small and homogeneous sample, the feedback has been encouraging and we intend to continue the project in the autumn. There are features such as browsing, PDF support and an internet connection, that need to improve before e-readers can enable efficient learning and researching in an academic setting. However, though many of the respondents still preferred the paper book, nearly all of them saw the e-reader as a future tool for studying.

As expected, those teachers with sparse experience of either the Kindle, the content of a specific e-book or the course, had few ideas on how to develop their courses. One month of e-reader usage seems to be too short a time period and the teacher test period should really start much earlier than the course. Consequently, in the future the project will focus on teachers and they will be offered a longer loan period.

The vision for the future of libraries is that students and teachers would be able to download library material easily from a distance on their own devices. For the time being e-books or e-readers are not a solution, especially because the vast majority of the libraries’ present e-book collections are not compatible with most of the e-readers, and the books read on e-readers are often available only for private customers. Logistic issues such as charging the batteries and preparing the e-readers also require a great deal of time and effort from the library staff, if the reading devices are lent to library patrons. However, if libraries want to become part of the development and the chain of distributing e-books, it is essential that they experiment with various e-book distribution models and e-readers.

The volume of e-resources increases every year and remote access to resources reduces the need to visit the library. This does not necessarily mean that libraries are less important than before, it merely represents a change in patrons’ needs. As the collections are more and more in digital format and the self-service increases, libraries have more resources to concentrate on the quality of service rather than the quantity. There is a greater need for information services, personal guidance and information literacy education than ever.

Finally, from our point of view the project can be considered a success merely because it got some of the teachers to rethink their methods of teaching and ways to develop the course. As a whole, the project shows that academic libraries can contribute to teaching methods by providing tools and support to teachers to develop their teaching methods and acquire new ideas and technology.

|

Aaltonen, M., P. Mannonen, S. Nieminen and M. Hjelt (2010): ‘A collaborative study: on the demands of mobile technology on

virtual collection development’, World Library and Information Congress: 76th IFLA General Conference and Assembly. 10–15 August 2010, Gothenburg, Sweden. http://www.ifla.org/files/hq/papers/ifla76/151-aaltonen-en.pdf.

|

|

Amazon.com, news release 19.4.2011: ‘Amazon.com Now Selling More Kindle Books Than Print Books’. http://phx.corporate-ir.net/phoenix.zhtml?c=176060&p=irol-newsArticle&ID=1565581&highlight=.

|

|

Ballhaus, W., M. van der Donk and P. Stokes (2010): ‘Turning the pages: the future of ebooks’, Technology, Media & Telecommunications, pwc. http://www.pwc.com/gx/en/entertainment-media/publications/future-of-ebooks.jhtml.

|

|

Clark, D. T., S. P. Goodwin, T. Samuelson, and C. Coker (2008): ‘A qualitative assessment of the Kindle e-book reader: results

from initial focus groups’. Performance Measurement and Metrics, 9(2), 118–129.

|

|

Collier, J. and S. Berg (2011): Student learning and e-books. In: S. Polanka (ed.), No shelf required: e-books in libraries (pp. 19–36). Chicago: American Library Association.

|

|

Cox, M. (2010): The changing nature of researching information technology in education. In: A. McDougall (ed.), Researching IT in education: theory, practice and future directions (pp. 11–24). New York, NY: Routledge.

|

|

Damast, A. (2010): ‘E-Book Readers Bomb on College Campuses’. BusinessWeek (June 11, 2010), 3.

|

|

Marshall, C. C. (2010): Reading and Writing the Electronic Book. Synthesis Lectures on Information Concepts, Retrieval, and Services #9, San Rafael, California: Morgan & Claypool Publishers.

|

|

Minčić-Obradović, K. (2011): E-books in academic libraries. Oxford, UK: Chandos.

|

|

Parment, A. (2008): Generation Y: framtidens konsumenter och medarbetare gör entré. Malmö: Liber.

|

|

Pattuelli, C. M. and D. Rabina (2010): ‘Forms, effects, function: LIS students’ attitudes towards portable e-book readers’.

Aslib Proceedings 62(3), 228–244.

|

|

Rogers, E. M. (2003): Diffusion of innovations. 5th ed. New York: Free Press.

|