of Special Collections and Archives

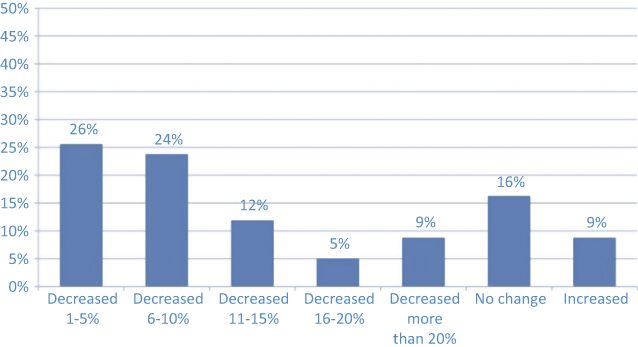

This paper summarizes the outcomes of the 2009 OCLC Research survey of 275 research libraries in the United States and Canada regarding the current status of their special collections and archives. The resulting report, Taking Our Pulse: The OCLC Research Survey of Special Collections and Archives, includes detailed analysis of the data and thirteen recommendations for community action. The three most common challenges named by respondents were space, digitization, and born-digital materials. Collections are growing dramatically, use of all types of material has increased, substantial backlogs remain, and 75% of library budgets have been reduced in recent years.

Special collections and archives are increasingly seen as elements of distinction that serve to differentiate an academic or research library from its peers. In recognition of this, OCLC Research conducted a survey of research libraries in the United States and Canada in order to determine the current state of special collections and archives.

A core goal of this research is to incite change to transform special collections. Therefore, in addition to analysis of the data, the published report of the project (Dooley and Luce, 2010) includes thirteen recommendations for action intended to press the special collections community forward. These are listed at the end of this paper.

As the report reveals, much rare and unique material remains undiscoverable, and monetary resources are shrinking at the same time that user demand is growing. The balance sheet is both encouraging and sobering:

-

Collections are growing dramatically

-

Use of all types of material has increased across the board

-

Half of archival collections have no online presence

-

While many backlogs have decreased, almost as many continue to grow

-

Management of born-digital archival materials remains in its infancy

-

Staffing is generally stable, but has grown for digital services

-

75% of general library budgets have been reduced

-

The current tough economy renders ‘business as usual’ impossible’

If such a survey were repeated in 2011, we have reason to believe that the percentage of respondents whose budgets have been reduced would be even higher, as would the extent of those reductions.

Figure 1: Change in overall library funding.

The three most often named ‘challenging issues’ in managing special collections were space, born-digital materials, and digitization.

The subject population encompassed the 275 libraries in the following five overlapping membership organizations:

-

Association of Research Libraries (124 universities and others)

-

Canadian Academic and Research Libraries (30 universities and others)

-

Independent Research Libraries Association (19 private research libraries)

-

Oberlin Group (80 liberal arts colleges)

-

RLG Partnership, U.S. and Canadian members (85 research institutions).

The rate of response was 61% (169 responses).

This paper summarizes selected data of potential interest to the European research library community, as presented at the LIBER conference in Barcelona on 30 June 2011. Results are presented in the following sections:

-

Metrics

-

Collections

-

User services

-

Metadata

-

Archival collections management

-

Digitization

-

Born-digital archival materials.

We were not surprised that the data confirmed a lack of established metrics for measuring special collections circumstances; this limits collecting, analyzing, and comparing statistics across the research library community. Norms for tracking and assessing collection counts, types and number of users, amount of materials used, metadata creation, archival processing, digital production, and other activities are necessary for measuring institutions against community norms and for demonstrating locally that primary constituencies are being well served.

When compared to the results of a survey of special collections across the membership of the Association of Research Libraries in 1998 (Panitch, 2001), our data show that collections have grown at an astounding rate. The mean number of both printed volumes and archival and manuscript collections has risen by an average of 50% in the aggregate since 1998. For two-dimensional visual, audio, and audiovisual materials, the increases range from 240% to 300%. The fact that two-thirds of libraries have some special collections materials in remote storage facilities is therefore not surprising.

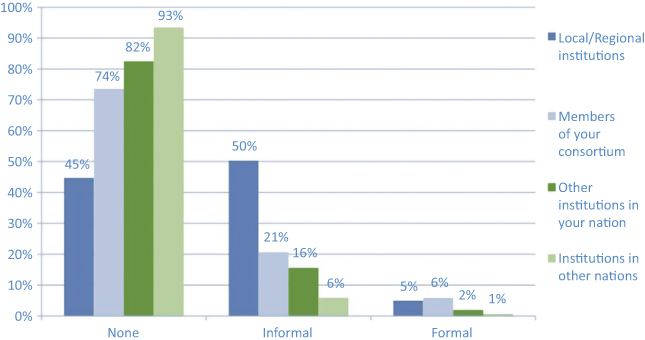

Collaborative collection development is an issue of substantial interest to, perhaps most particularly, research library directors, given the problems that arise when materials are inappropriately acquired, when competitive situations arise between institutions, or when great abundance in collecting leads to inadequate storage space. Our data show that roughly half of respondents engage in such collaboration informally, generally on a regional basis, while very few have formal agreements. Investigation of the nature and success of existing cooperative arrangements is an area ripe for research.

Figure 2: Collaborative collection development.

User services are particularly rich in issues of current interest, including levels of use, affiliations of researchers, effective communication with users, accessibility of materials in backlogs, cost-effective loan of both originals and reproductions, and new methods of outreach to foster widespread and meaningful use. These issues are of particularly potent interest because successful delivery of materials to users is widely accepted as the ultimate raison d’être of library collections.

The lack of metrics noted above is particularly noticeable in our data for the number of on-site users of special collections: 43% of users were categorized as ‘other’ rather than being slotted into a particular user category (faculty, students, visiting scholars, etc.). This suggests that many libraries do not track who is using their collections, which can be problematic in making the case that primary constituents are being served.

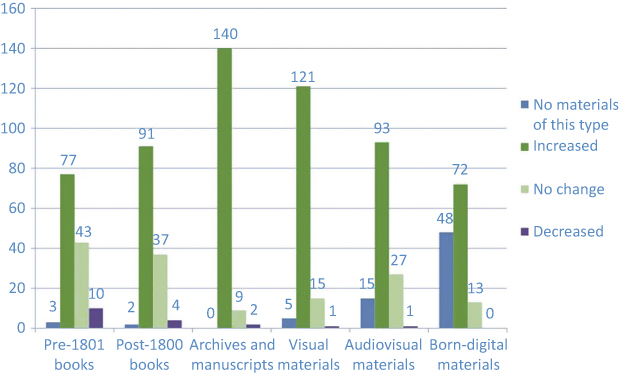

The data also reveal that use of materials has increased in the past decade. The percentage of respondents reporting increases varies by type of material: examples include 84% for archives and manuscripts, 71% for visual materials, 70% for audiovisual materials, and 54% for post-1800 printed books.

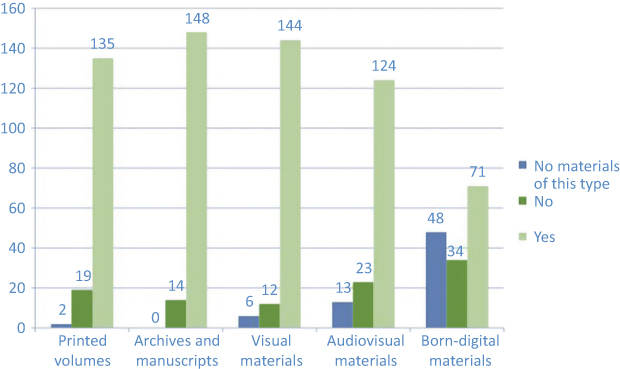

Figure 3: Changes in use by format, indicated by number of respondents.

A strong majority of respondents have policies permitting users to access uncataloged and/or unprocessed materials: depending on the format, 73–88% permit access (the exception is born-digital material, to which 42% permit access until the files are brought under proper management). We do know, however, that requests for access are not always granted; the most common reasons include the difficulty in using materials received in serious disorder, the potential for endangering fragile materials not yet properly protected, and the need to identify materials that should be restricted for reasons of privacy or confidentiality.

Figure 4: Access to uncataloged or unprocessed materials, indicated by number of respondents.

The question of whether users should be permitted to employ personal digital cameras to take photographs of special collections materials while working in a reading room has been a vexed one in recent years in U.S. research libraries. We learned, however, that 87% of our respondents already permit this, and we know anecdotally that more have established such policies in the last year. Those who do not permit cameras most commonly cite the following reasons: the potential for copyright infringement, improper handling of materials, loss of revenue from in-house reproduction services, and a sense that existing methods of preparing surrogates of original materials meet user needs.

Special collections libraries increasingly are coming under pressure to participate in interlibrary loan programs by loaning original materials in order to maximize use of these materials as much as feasible in service to research and teaching. We learned that 44% of respondents loan reproductions, while more than one-third loan original printed volumes and nearly another one-third do not loan at all. Requests for loans generally receive curatorial review, and approvals are selective.

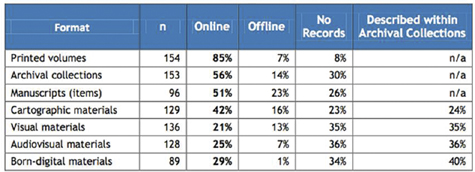

For the past decade the chief mantra related to special collections has been that we must do everything possible to ‘expose hidden collections.’ Based on a comparison of our data with a similar project conducted by the Association of Research Libraries in 1998, significant progress has been made — but the work is far from finished. As seen in Figure 5, 85% of printed volumes have an online catalog record, but only half of archives and manuscripts are represented online, while this falls to as low as 25% for audiovisual materials. (Note: In the U.S. it is common practice to create a MARC21 record for an archival or manuscript collection, just as it is for a book.)

Figure 5: Catalog records.

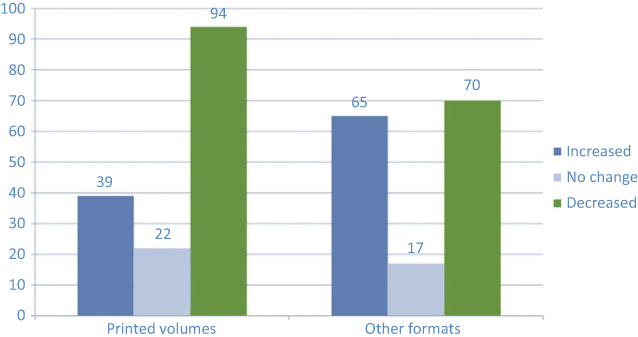

As the work of cataloging continues apace, an important related issue is whether or not backlogs of materials have decreased — a particular challenge given the rapid growth in collections that was cited earlier. It was therefore somewhat encouraging to learn that 56% of backlogs of printed volumes have decreased in size. In contrast, only 41% of backlogs of other materials have decreased.

Figure 6: Changes in size of backlogs.

Clearly it is a challenge to keep up with the in-flow of new materials, and many libraries are losing the battle. Library administrators have decreasing patience with this scenario yet rarely are able or willing to allocate new resources to accomplish the work. Special collections libraries must do more with the same or fewer resources as they have had in the past.

Just as only half of archival and manuscript collections have an online catalog record (usually in MARC21 within a standard online library catalog), less than half (44%) of collections are represented by an archival finding aid available via the Internet. On the other hand, 30% of collections do have a finding aid that is available only within the owning library; these may be on paper, in a word processing file, or in a local database. We note that the percentage of collections discoverable online would increase to nearly 75% if those offline finding aids were converted.

Archivists and special collections librarians in the U.S. recognize that making more archival collections both discoverable and available for use is of paramount importance; the magnitude of existing backlogs does not speak well for effective management of these materials. An influential paper published in The American Archivist in 2005 has been an enormous catalyst in influencing archives to simplify the processing of their collections in order to do so more rapidly and efficiently (Greene and Meissner, 2005). We learned that 18% of respondents always use such simplification techniques, while more than half do so sometimes.

One possible reason for low productivity in archival processing is that no standard software tools for creating finding aids exists. Methods of inputting data often are inefficient, data cannot always be re-used to create outputs other than a traditional finding aid, and it may be difficult to export the data from a local database to one that is available via the Internet. One software tool that meets such requirements is gaining traction, however: the Archivists’ Toolkit, which is used by one-third of our respondents (Archivists’ Toolkit, 2011).

Use of Encoded Archival Description has become widespread since its original publication in 1998: two-thirds of respondents employ it.

Rare and unique materials in special collections libraries are the usual fodder for digitization projects, and our data confirm that nearly all (97%) have completed one or more projects; about half have an active program of digitization in place. Special collections staff is deeply involved in all core activities — above all, in selection of content (99%), but also project management (87%), metadata creation (84%), and digital image production (71%).

OCLC Research has actively encouraged an approach to digitization that favors access over preservation as the core motivation, recognizing that many archival materials are in formats that do not warrant publication-quality reproduction for a variety of reasons. This is the central tenet of our report Shifting Gears, which has proven catalytic in encouraging a shift from the highly selective ‘boutique’ projects that formerly prevailed to projects that digitize entire collections, using methods that enable high levels of production (Erway and Schaffner, 2007).

One-third of survey respondents indicated that they have done such large-scale projects — a result that has proven questionable after follow-ups have revealed that the quantity of digital images produced and/or the rates of production were in fact not impressive. In order to draw attention to methodologies that have been more successful, in spring 2011 we published Rapid Capture: Faster Throughput in Digitization of Special Collections (Erway, 2011). This report presents case studies of approaches to large-scale image capture for materials in a variety of original formats, including photographs, audio, medieval manuscripts, and institutional archival records.

We also explored the extent to which respondents have licensed content to commercial publishers as a means of having their collections digitized. Twenty-six percent (26%) have done so. Due to the degree to which such agreements prevent open access to important content, the Association of Research Libraries has published principles to guide research libraries in their relationships with publishers and vendors (Principles, 2010).

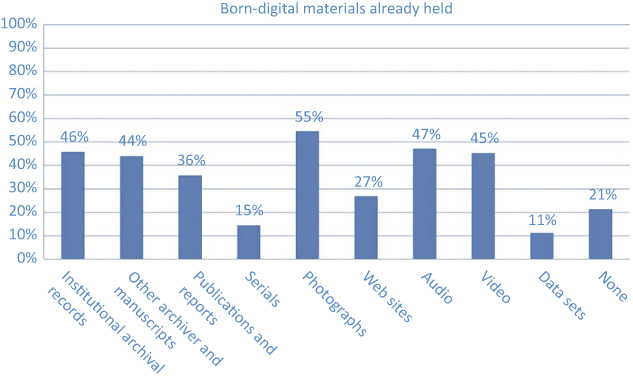

In addition to the challenges associated with digitization, the daunting challenges of managing born-digital archival materials have begun to loom large among the concerns of academic and research libraries. Simply stated, we learned that within the context of the research library community, born-digital materials have to date been under-collected, many institutions do not know how much material they have, true preservation capabilities generally are not yet in place, and few materials are accessible for use.

Born-digital materials in one or more formats have been collected by 75% of respondents; these data are in stark contrast to the 35% who reported the size of their born-digital holdings. Visual and audiovisual materials (such as photographs, audio, and video) are the most frequently collected born-digital formats, closely followed by institutional records and other archives and manuscripts. Our analysis of the data relating to born-digital management leads us to surmise that collecting of these materials to date has generally been passive, sporadic, and limited.

More than half of respondents cited three impediments to progress: lack of funding, expertise, and time for planning. Lack of funding may be somewhat of a red herring, since the costs of born-digital management and preservation have been little studied, and some activities can be undertaken with few or no new resources.

Figure 7: Born-digital materials already held.

As stated earlier, digitization and born-digital materials were two of the three most frequently stated ‘most challenging issues’ in managing special collections. In addition, 83% cited a need for more staff education in born-digital management.

OCLC Research has just launched a project that will explore the relationship between ‘born-digital’ and special collections, including the ways in which archival expertise is crucial in managing born-digital materials. We will also outline initial steps that can be taken to inaugurate a modest program to bring born-digital materials under basic control (Born-digital, 2011).

In addition to mapping the current landscape of special collections and archives in research libraries, we sought to develop an action agenda for the research library community in the United States, as embodied in these thirteen recommendations:

-

Establish metrics for standardized measurement of key measures.

-

Identify barriers to and goals of collaborative collection development.

-

Take collective action to preserve at-risk audiovisual materials.

-

Liberally implement access and interlibrary loan approvals.*

-

Adopt sustainable methodologies to stop the growth of backlogs.*

-

Develop shared metadata capacities for maps and printed graphics.

-

Convert legacy finding aids without revising or upgrading.

-

Develop models for large-scale digitization of special collections.*

-

Identify the scope of and gaps in the corpus of digitized rare books.

-

Identify the relationship between born-digital materials and special collections.*

-

Determine basic steps for jump-starting management of born-digital materials.*

-

Develop use cases and cost studies for born-digital materials.

-

Confirm high-priority areas for education and training and fill the gaps.

This is meant as an agenda for the entire special collections community, not for OCLC Research. Some actions may be appropriate for library consortia, others for individual institutions, and still others for professional societies. We do, however, currently have projects underway to address the five starred (*) items (Mobilizing, 2011).

It is possible that a very different set of recommendations could emerge from analysis of the circumstances across the European community of research libraries.

As of June 2011, we have begun to collaborate with Research Libraries UK (RLUK) on a similar project to survey its membership. Members of the OCLC Research Library Partnership in the UK and Ireland will be included in the population, as will selected other institutions that have particularly distinguished special collections. RLUK has recently developed an ambitious work agenda focused on Unique and Distinctive Collections, and the survey data will be helpful in focusing their efforts.

What about the rest of Europe? Would there be high value in a similar project, or projects, to study the LIBER population? The membership is disparate and far-flung across the geographic and institutional landscapes such that a LIBER-wide project could be difficult to design, and the data could be somewhat amorphous. Would nation-specific surveys be valuable? Regional? By type of library? OCLC Research would be delighted to explore the possibilities with the LIBER leadership.

|

Archivists’ toolkit: By archivists, for archivists (2011). Project website,

http://www.archiviststoolkit.org/.

|

|

Born-digital special collections (2011). OCLC Research project description.

http://www.oclc.org/research/activities/borndigital/default.htm.

|

|

Dooley, Jackie M. and Katherine Luce (2010): Taking Our Pulse: The OCLC Research Survey of Special Collections and Archives. Dublin, Ohio: OCLC Research, http://www.oclc.org/research/publications/library/2010/2010-11.pdf.

|

|

Erway, Ricky (2011): Rapid Capture: Faster Throughput in Digitization of Special Collections. Dublin, Ohio: OCLC Research, http://www.oclc.org/research/publications/library/2011/2011-04.pdf.

|

|

Erway, Ricky and Jennifer Schaffner (2007): Shifting Gears: Gearing Up to Get Into the Flow. Dublin, Ohio: OCLC Programs and Research, www.oclc.org/programs/publications/reports/2007-02.pdf.

|

|

Greene, Mark A. and Dennis Meissner (2005): ‘More product, less process: Revamping traditional archival processing.’ The American Archivist 68:2, 208-263, http://archivists.metapress.com/content/c741823776k65863/fulltext.pdf.

|

|

Mobilizing unique materials (2011). OCLC Research work agenda,

http://www.oclc.org/research/activities/mum.htm.

|

|

Panitch, Judith M. (2001): Special collections in ARL libraries: Results of the 1998 survey. Washington, D.C.: Association of Research Libraries, http://www.arl.org/bm~doc/spec_colls_in_arl.pdf.

|

|

Principles to Guide Vendor/Publisher Relations in Large-Scale Digitization Projects of Special Collections Materials (2010). Association of Research Libraries. Policy approved July 2010.

http://www.arl.org/bm~doc/principles_large_scale_digitization.pdf.

|