Evidence from the UK

The last decade has been a period of unprecedented change for university libraries. The rapid growth in numbers of students and staff across the university sector has been accompanied by the move to a substantially digital environment with some fundamental changes in how libraries and their users operate. During this period, most university libraries have seen continued growth in their budgets in real terms, but libraries now face a period in which they will have to cope with continued rapid, perhaps transformational, change, accompanied by reductions in their budgets. This paper is based on evidence gathered and analysed by the Research Information Network on the financial position of university libraries in the UK, and how they are dealing with the prospect of cuts. It highlights two related challenges for libraries: developing and enhancing relationships with their users, and developing new services to maximise their value to users.

The last decade has been a period of unprecedented change for university libraries. The rapid growth in numbers of students and staff across the university sector has been accompanied by the move to a substantially digital environment with some fundamental changes in how libraries and their users operate. Further change is on the way, with unpredictable implications for students, academic staff, and for libraries.

As they have responded to new developments over the past decade, and changed their operations, most university libraries have seen continued growth in their budgets in real terms. The next few years are likely to prove much more difficult in financial terms. Libraries therefore face a period in which they will have to cope with continued rapid, perhaps transformational, change, accompanied by reductions in their budgets.

This paper is based on evidence gathered analysed by the Research Information Network on how university libraries in the UK in particular are dealing with this new situation. It highlights two related challenges for libraries.

First, users’ demands for content have increased enormously over the past decade, in response to the greatly increased supply of content available to them 24/7. But the demand is unrelated to price, because users — at least in the UK — do not pay; the library does. At the same time, many users — particularly academics — believe that libraries and the services they provide have become less relevant to their needs. Hence many are less willing than previously to see library budgets sustained at the expense (as they see it) of their own departmental budgets. Disintermediation thus has the power to hit libraries in a number of different ways, and a key challenge is to develop and enhance relationships between libraries and their users.

Second, research libraries in particular face a tension between sustaining their traditional roles of looking after and providing access to scholarly content on the one hand, and providing more content and new services in a digital environment. In what remains a hybrid world, at least some of the traditional roles remain valuable to many users. But developing new services is essential if libraries are to maximise their value to users in a rapidly-changing world.

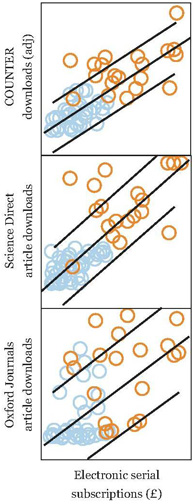

Between 1998 and 2008, expenditure on all university libraries in the UK grew by 30% in real terms,[1] with even faster growth — at nearly 48% — shown by the libraries of the research-intensive universities represented by Research Libraries UK (RLUK).[2] Numbers of staff and students also increased, however; and income and expenditure on research grew even faster. Hence, as shown in Figure 1, the proportion of total university expenditure that went to support libraries fell: from 3.4% to 2.8% across all UK universities, and from 3.2% to 2.6% across the RLUK libraries. So libraries represent a declining share of university budgets.

Figure 1: Library expenditure as a percentage of overall institution expenditure 1998–2008.

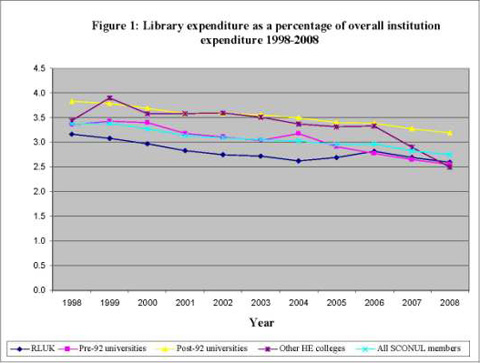

Over the past two years, however, libraries have begun to experience a much harsher financial climate. A survey for the Charleston Observatory in 2009 showed that libraries across the world were facing cuts. In the US, the growth in library budgets in the years up to 2008 seems to have been somewhat slower than in the UK: statistics from the ARL suggest that its university members saw an increase of 12% in real terms in their budgets between 2001 and 2007. But two-thirds of them experienced cuts in 2008–09 and 2009–10, with a mean of 5% and a maximum of over 20%. The Charleston survey[3] showed a similar picture, indicating that over 45% of US libraries had experienced cuts in 2009, and over 40% were anticipating cuts in future years.

As shown in Figure 2, budget cuts have been rather slower to arrive in the UK, but over 53% of libraries expect cuts in 2010–11. And they are especially gloomy about prospects for the future, with nearly 57% predicting further cuts in 2011–12. In such circumstances, there is renewed attention to the balance of expenditure between staffing, content and services. The proportions of library budgets spent on these three key elements vary hugely across the university sector in the UK, as we shall see, but there is a widespread view that in libraries where staff represent a relatively high proportion of expenditure, that proportion will have to fall.

Figure 2: Expectations of Budget Cuts.

In seeking to address the new economic situation, library directors are planning to make cuts in services, staffing, infrastructure and content provision.

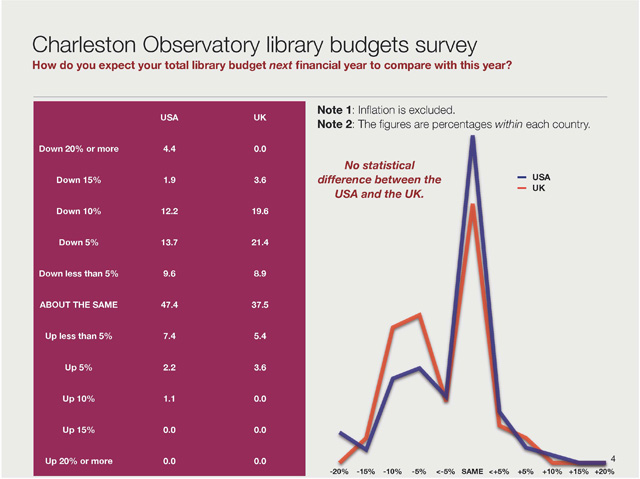

Staffing represents over 50% of expenditure overall across all UK university libraries, although there are significant differences between individual libraries — proportions vary between under 30% and over 70% — and groups of libraries. The proportion tends to be highest in smaller colleges and in specialist institutions. Across all UK libraries, staff numbers rose by about 15% between 1998 and 2008, and, as shown in Figure 3, expenditure on staffing rose in real terms even faster, by over 30%, with the sharpest rise — at 45% — in the research-intensive universities. Again, however, it should be noted that the numbers of academic staff and students — the prime users of university libraries — grew almost twice as fast as library staff numbers in this period.

Figure 3: Indexed real terms expenditure on staff 1998–2008.

In a context where the demands on libraries and their staff have increased, UK university library directors believe that their staffing levels have already been pared down. But senior managers in universities in the UK and the US are planning cuts in staffing, including academic staff, and it is not surprising that they see scope for cuts in libraries too. Hence nearly three-quarters of UK library directors — a significantly higher proportion than their US counterparts — believe that they will have to make cuts in the numbers of library staff.

But doing more with fewer staff represents a significant challenge for library directors, and many have spoken of the need to think in terms of re-engineering and introducing new staffing structures in order to help in ensuring that they focus resources on those areas that have the biggest impact: speedy delivery of the information resources and services that accurately meet the needs of students and academics. Reductions in staffing levels should thus ideally be based on increased understanding of the relationships between activities, costs and impact, and be combined with more effective performance management so that library staff have a clear view of their roles, along with a willingness to take on new ones and to learn new skills.

Libraries are familiar with the experience of restructuring, for example in merging with IT services. But there are tensions between the desire for fully thought-through re-engineering to deliver more effective and efficient performance on the one hand, and the need to reduce staff numbers quickly in response to budget cuts on the other. Evidence so far is that the favoured methods for achieving cuts in the current crisis is by introducing recruitment freezes and not replacing staff who leave.

Service levels are of course closely related to staffing, but librarians are understandably reluctant to cut services to staff and students. Responses to the Charleston survey and focus group discussions, however, show that UK library directors across the sector believe that budget cuts at the levels they are being asked to consider cannot be achieved without a significant impact on services. Reductions in opening hours, particularly at weekends and during vacations, are options being considered by many libraries, and some directors wonder whether they can sustain the 24-hour opening that has become common, especially during the exam season. Some libraries are already reducing opening hours, even though this is unwelcome to many students.

Other options being considered include reductions in subject support for academic staff and students, and in information skills training, in addition to cuts in the purchase of books and of journals. And budget cuts many make it difficult to sustain newer developments such as promoting changes in scholarly communications, or supporting the information gathering required for research assessment purposes. It is also clear that some libraries are postponing IT and other projects for the development of their infrastructure of services, along with plans for new building work.

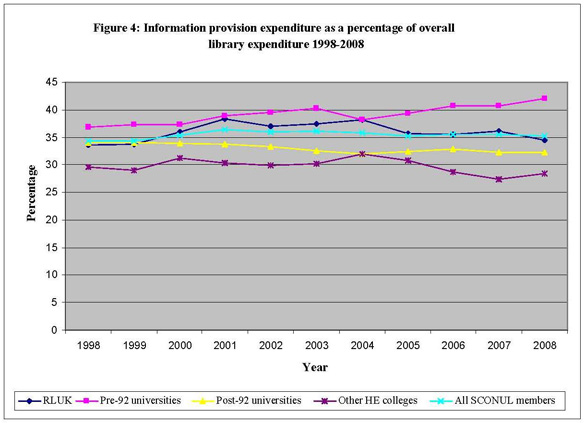

Expenditure on information content of all kinds represents about 35% of all library expenditure across the UK university library sector, and that proportion has been relatively stable over the past decade. At a number of universities, there have been policies to protect the budgets for information resources above all else, partly in order to sustain and improve the student experience. Again there are significant differences between individual libraries and groups of libraries, essentially representing the mirror image of the different proportions of their expenditure accounted for by staff. The proportion tends to be highest — at around 37% — in universities established before 1992, although it is slightly lower among the most research-intensive universities.

Figure 4: Information provision expenditure as a percentage of overall library expenditure 1998–2008.

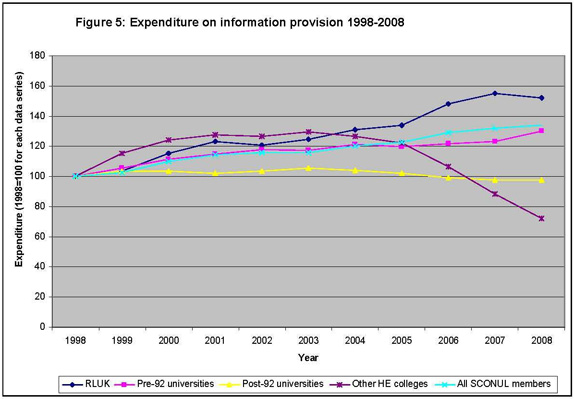

The relatively stable proportion of expenditure on content implies, of course, increases in actual expenditure in real terms. But here experiences differ across the sector, as shown in Figure 5. In the research-intensive universities expenditure rose by 52%, but in the newer universities, after rising by 5% in the years up to 2002, expenditure on content has actually declined in real terms since then, and in 2008 was actually 2% lower than it was in 1998.

Figure 5: Expenditure on information provision 1998–2008.

Expenditure on books, both printed and electronic, fell from 12% to 9% of overall library expenditure across all UK universities between 1998 and 2008, and actual expenditure fell by 10% in real terms. These falls occurred even though students have a powerful voice in demanding that universities should provide access through their libraries to the books included on course reading lists. US university libraries experienced similar falls, though it should be noted that US students are generally more prepared than their UK counterparts to purchase copies of key texts for themselves.

There is a widespread belief — or hope — that e-books may ease the problems that libraries face in meeting the demands for books — particularly for text-books and course readers, and important experiments are under way in the UK in the form of an e-books observatory project.[4] Many librarians express a sense of inevitability about a transition to e-books, and this feeds a view, represented in the Charleston survey and in RIN focus groups, that cuts in their provision of content will fall disproportionately on printed books.

But librarians are also aware of the constraints against a wholesale move to e-books. Many monographs and other books are not yet available electronically; business models and publishers’ policies on pricing and accessibility are complex, inconsistent and difficult to comprehend; and despite the arrival of the i-pad and other devices, the technical problems relating to reading long books on screen have not yet been resolved to universal satisfaction. It is thus difficult for libraries to customise collections to meet the needs of their users, and the many different platforms for e-books make it less than straightforward for libraries and users to navigate through the various interfaces. These constraints, coupled with concerns about preservation of scholarly materials in digital form for the long term, have limited the take-up of e-books; and there is also a widespread view that libraries need to work together with publishers to promote innovative thinking on new models and routes to content.

It is well-known that expenditure on scholarly journals and other serials has risen fast in recent years. Across the UK it rose by 59% between 1998 and 2008, and by 87% in the research-intensive universities. It now represents nearly 19% of overall library expenditure, having risen from just over 15% in 1998, and in many well-established university libraries it accounts for over a quarter of the overall budget.

Big deals have increased enormously the range of titles available to members of universities in all parts of the sector. They have also changed expectations. Readers — academics in particular — now expect to have immediate access to most of the journals in their specialist area, and libraries find that nearly all of the titles to which they now subscribe are read, even if only by small groups of readers. Any suggestion of major cuts in the portfolios of journals to which libraries subscribe thus gives rise to vocal hostility.

Nevertheless, there is a widespread belief that current levels of journal provision may be unsustainable, especially for some smaller institutions and those which are teaching-led. There is intense pressure to reduce costs by abandoning print copies of journals, and cancelling subscriptions to lowly-used titles. Libraries are thus looking intensely at usage data before making decisions on renewals, and in some less-well-funded institutions especially, the prospect is that some big deals will be cancelled.

Libraries are also looking very closely at the costs of the big deals and how they might be reduced, for they view the seemingly inexorable increases in the prices charged by publishers as unsustainable. For UK libraries, most of the deals with the larger publishers are negotiated through regional consortia or centrally through the Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC), under its National Electronic Site Licensing initiative (NESLi2). Individual libraries then decide whether or not to subscribe to the deal. Although the negotiations are conducted by professionals, some members of our focus groups — especially those from teaching-led universities — are concerned that the deals do not represent good value for them, and are considering the possibility of negotiating individually with publishers on their own account.

But there are also concerns about the confidentiality clauses that seek to prevent universities from sharing with each other information about the costs of the deals they reach. Many library directors consider themselves involved in a war of attrition with publishers, and there are some suggestions of concerted action to tackle the lack of transparency about the terms of big deals. Nevertheless, librarians are aware of the risks if they try to break ranks, not least because the UK is a relatively small part of the global market for publishers. In other parts of the world, especially China and India, publishers are experiencing growth in their markets.

Hence only by acting in concert with others both in the UK and overseas do libraries see much chance of achieving significant savings in their deals with publishers. There is thus in the UK increasing interest in the possibility of site licences covering the whole university sector and especially in the pilot initiative to that end in Scotland (SHEDL). Achieving such deals across the sector as a whole will not be straightforward, especially in a financial climate which is likely to intensify opposition from senior managers in universities towards ‘top-slicing’ of the funds provided to individual universities. Thus the diverse positions and financial prospects of different universities may make it more difficult for the sector as a whole to work together towards common goals, and students and staff in smaller or less-well-resourced institutions may find that they have access to a reduced range of journals. Nevertheless, it is important that libraries should work together and with publishers to find ways of reducing the costs of licence deals and the restrictions on access often associated with them.

Academic libraries in all parts of the sector have developed in the past decade new kinds of activities in supporting research, teaching and learning, and senior librarians are very much aware of the need to sustain the momentum of innovation in developing new approaches and new services to support changes in institutional missions and in the workflows of both students and staff. But the scope for doing so may become increasingly constrained by financial cuts and loss of key staff; sustaining momentum will depend increasingly on co-operation across the sector.

Even the most well-resourced libraries cannot hope to acquire and provide access to all the content that their academics and students might want. Any such aim is especially otiose in an environment where users can find content from multifarious sources on the internet. Selective development of their collections thus remains a fundamental part of the role of academic libraries. But there is increasing interest in moving from a ‘just-in-case’ to a ‘just-in-time’ approach, and from library-controlled to user-generated acquisitions, particularly in the light of evidence that the latter circulate at least as widely — and often more so — than the former.

The shift in university libraries away from print and towards digital content is driven by powerful forces including the constraints of space and finance, and above all user demands. In the short term, however, most university libraries in the UK are likely to remain hybrid, with both print and digital content. For despite the progress of digitisation and the increasing preponderance of born-digital content, we are still far from the position where all the content of interest to students and researchers is available digitally, and many of them are reluctant to abandon print altogether.

In a hybrid world, some libraries are interested in exploring how they might build co-operative, distributed models for library collections — both digital and in print — that are shared across a group of libraries, regionally, nationally, or defined by their subject interests. Low-use print material can thus be shared by users across a number of libraries, and locally managed collections replaced by co-operative agreements. For digital material, there is increasing interest in moving towards co-operative collection-development plans and co-operatively managed digital aggregations, or even ‘cloud-sourced’ collections.

One potential way of reducing the pressure on acquisition budgets and of enhancing access to content, of course, is through the provision of open access, through either the green or the gold route. Librarians in the UK have played a leading role in promoting open access initiatives, through the establishment of institutional repositories and of arrangements for the payment of open access publication fees. In the very long term, it is possible that open access may help in reducing the pressure on library budgets. But over the next 3–5 years at least, open access initiatives will continue to represent additional burdens on libraries, for the costs of running repositories and promoting their use, or of paying publication fees, are not being offset by any significant reductions in subscription costs for scholarly journals.

The shift from print to digital resources provides libraries with the opportunity to focus more on providing services than on managing collections of content. Many libraries are keen to develop in this way, with new services to help users create, manage and manipulate information. Libraries are thus interested in helping to develop more effective arrangements for managing, curating, sharing and preserving data created or gathered by researchers. Similarly, they have also been active in addressing the increasing concerns about lack of understanding and skills among academics as well as students in handling an ever-more complex information environment.

If they are to develop new services or enhance existing ones, however, libraries must tackle three key challenges.

-

First, they must reduce if not eliminate what is routine in order to make space for new activities, for it is unlikely that additional resources or funding will be available. Outsourcing of what can be done more efficiently or effectively by others is likely to be part of the answer in areas including cataloguing and the hosting of library websites.

-

Second, they must ensure that users are fully engaged in the development and implementation of new services.

-

Third, they must develop new models of working co-operatively to exploit the resources and expertise of their colleagues in the sector as a whole. A recent project sponsored by SCONUL to develop a business case for shared services for all UK university libraries is a significant example of work of this kind.

Increasingly, librarians are being required to take on a variety of roles and activities. The ICT infrastructure for libraries is becoming ever more complex, and libraries are likely to need more computer scientists and informaticians to work along with subject experts.

There is a growing recognition among senior managers in universities as well as information professionals that both academics and students require better support if they are to handle information resources effectively. But effective support depends increasingly on a mixture of subject specialist and information expertise; and there is no consensus on how moves of this kind might be initiated, nor on how professionals of this kind might be organised and where they might be located within institutional structures.

A minority view among senior managers is that libraries and librarians are key to these kinds of developments: that they already understand and have a broad view of the issues which other players lack, and that some of them are already involved in providing relevant services as well as acting as partners in pilot projects. A more widespread view is that while many librarians have talked about developing their contribution to the research effort in these ways, there are only weak linkages between the expertise and the services now needed and the traditional skillsets of librarians. Even those who take a more positive view acknowledge that if librarians are to develop their roles in this way, there will be a huge need for training and capacity-building; and that might involve re-envisioning and rebuilding the role of subject specialist librarians.

There is a strong feeling among senior librarians that they have failed effectively to communicate the value of their services to those who fund and use them. They believe that many senior managers in universities, as well as academics and students, have outdated views and expectations about the services that libraries now provide. There is thus an increasing risk that much of what libraries actually do may be invisible in a virtual environment. This may leave libraries especially vulnerable when institutions have to take difficult financial decisions, with cuts targeted at specific departments or areas of activity. Moreover, while the student voice in support of libraries may be particularly powerful, it tends to be focused on a rather narrow set of issues relating to ready access to course texts and the need for extended opening hours.

In current circumstances it is particularly important that libraries should be able to show not only that they are operating efficiently, but that they provide services with demonstrable links to success in achieving institutional goals. Return on investment is thus an increasingly important issue. It is important therefore that libraries are proactive in seeking to understand user behaviour and workflows; and in rigorously analysing and demonstrating the value of their activities in improving students’ experience and in supporting teaching, learning and research.

The focus of performance indicators up to now has tended to be on inputs and outputs that are relatively straightforward to measure, rather than addressing the much harder issues relating to impact and value. Nevertheless, it is essential that more is done to analyse the relationships between library activities on the one hand, and learning and research outcomes on the other.

Work of this kind is in its relatively early stages, and it is fraught with difficulties. Gathering and analysing evidence of value is notoriously difficult. A number of different approaches have been adopted, and there is no single answer. A key question is ‘value for whom?’ In relation to libraries, approaches to gathering evidence of value for students or academics may well differ from approaches to value for funders or for universities. Similarly, approaches to the value of existing services may not be appropriate in gathering evidence of possible changes either to the nature or to the level (positive or negative) of those services. And there are notorious difficulties presented in assessing changes in value over time.

One simple approach is to analyse expenditure and usage, to ascertain the unit cost per usage and its variation between different resources and institutions, or over time. Analysis of the costs per download of e-journals in UK university libraries shows some intriguing patterns. As shown in Table 1, downloads rose by over 160% between 2004 and 2008, and by 250% in the research-intensive universities.

Table 1: UK Higher Education Libraries Annual E-journal Downloads

| Average for sector | |||||

| Year | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 |

| Russell Group | 783,870 | 1,377,603 | 1,846,121 | 2,211,245 | 2,795,825 |

| Other Pre-1992 universities | 439,813 | 632,144 | 665,926 | 819,335 | 1,001,521 |

| Post-1992 universities and other institutions | 283,760 | 322,251 | 443,027 | 521,350 | 592,253 |

| Total | 432,693 | 632,758 | 772,600 | 930,415 | 1,134,165 |

| Index 2004=100 | |||||

| Russell Group | 100 | 175.7 | 235.5 | 282.1 | 356.7 |

| Other Pre-1992 universities | 100 | 143.7 | 151.4 | 186.3 | 227.7 |

| Post-1992 universities and other institutions | 100 | 117.1 | 156.1 | 183.7 | 208.7 |

| Total | 100 | 146.2 | 178.6 | 215.0 | 262.1 |