The Anatomy of a Crime Discovery after 25 Years. A Notable Case of Book Theft and its Detection

Jesper Düring Jørgensen

Chief security advisor, The Royal Library, PO Box 2149, DK-1016 Copenhagen, Denmark

jdj@kb.dk [1]

The story

The 11th September 2003 was quite an ordinary working day in the Royal Library - at least for the first few hours in the morning. At approximately 11.00 a.m., however, I was interrupted by the telephone. A polite lady introduced herself as the rare book specialist from Christie’s in London. From a consignor she had received the following work for sale: Propalladia de Bartholome de Torres Naharro. Dirigida... Napoles: por Ioan Pasqueto de Sallo, Naples 1517. Her investigation of a critical edition of Torres Naharro’s works from 1943 had established that only two copies of this particular work were known to exist. One incomplete copy in the National Library of Spain in Madrid, and one complete copy in The Royal Library in Copenhagen. This puzzled the keeper of books at the auction company, and she was keen to know whether she had a historic sensation in her hands or simply a stolen book.

Unfortunately, I had to inform her that this extremely rare book had been missing from the collections of the Royal Library since 28th February 1979. On that particular day the systematic revision of our collection of older, foreign printed books - caused by the regrettable fact that the Royal Library had been subjected to a number of thefts in the 1970s - had reached volume 18, p. 36, of our systematic shelf-list. These figures also form the shelf-mark of the book. I therefore asked whether there were any traces of any library shelf-mark in the left-hand corner on the inside of the binding. The answer was at first in the negative, but when I asked my conversation-partner to turn the book more towards the light, she was then able to read some numbers. It became quite obvious that an attempt had been made to erase the shelf-mark of the Royal Library. It was still legible, however: 18, – 36, when the book was held in the correct position towards the daylight.

This was a moment to be remembered. For thirty years the police and the security organisation of the Royal Library had been without any trace of either the thief, who it was considered must have been an insider, or the books, which until now had not appeared on the market. Up to that day we had not been able to identify any copy of the stolen titles among the books, which from time to time appeared in auction or antiquarian catalogues. In the course of our conversation it became clear that the same consignor had delivered three more books for sale, among these a Luther edition from 1525 which was also missing from our collection of early printings from the Lutheran reformation. The binding of this copy was stamped with the Danish coat of arms in a way,which is typical for books from The RoyalLibrary. After a few further conversations on the phone and the receipt of a fax from Christie’s with pictures of the characteristics of the bindings of the books in question and of the special coats of arms, I informed the director general of the Royal Library about the astonishing development in this old case. This was not, however, that easy to do, as Erland Kolding Nielsen was taking part in an important meeting in Jutland, in which the subject was the future of cultural politics for the research libraries in Denmark. At last, however, he came to the telephone and immediately ordered me to go to London as soon as possible and although this was a little impolite to Christie’s, I invited myself and the librarian who had been in charge of our revision of the foreign collection to come to London as soon as possible to investigate the matter. In this way I acquired a highly qualified witness, as no one else in the Royal Library had ever had so many of our rare books in her hands.

Before our departure I contacted the local Interpol office in Copenhagen and informed the head of the office that some of the stolen books had come to light at Christie’s. My intention was that the Copenhagen police via Interpol would be able to inform Scotland Yard, should complications arise at Christie’s. Four days later, on the 15th September at Christie’s, we were presented with not merely four books but a total of sixteen, all of which had been delivered by the same consignor. Let me make no bones about this: we were rather curious to know the identity of this particular consignor but whether we asked in a tactful manner or tried to persuade our host in a more persistent way, it did not help at all. At last I decided to phone Interpol in Copenhagen and the result of this call was another one to the Arts and Antique Squad at Scotland Yard. The conclusion of our negotiations was that the security chief at Christie’s guaranteed that the books would under no circumstances be handed back to the consignor or sold, for we had been able to prove that each one of the sixteen books was property stolen from The RoyalLibrary.

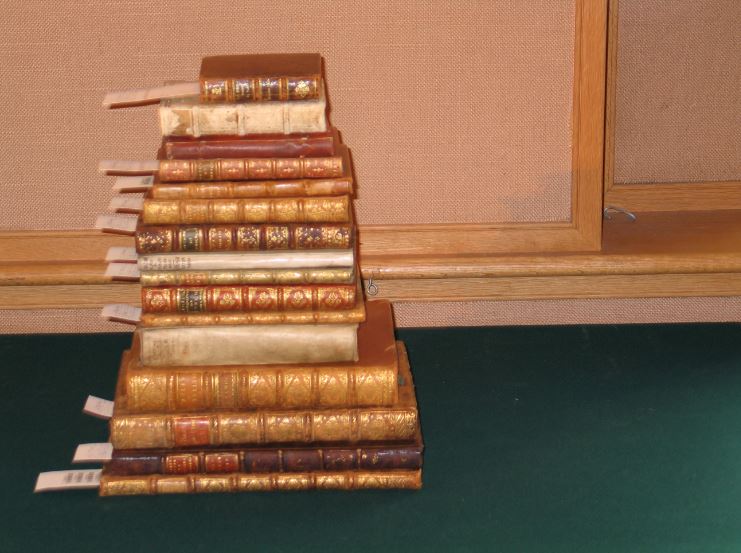

Figure 1: The pile of sixteen books at Christie’s.

In the course of my work as a chief security advisor I have often seen stolen books, as well as other stolen items. It is always typical that stolen books tend to look worn and it is normally obvious that they must have passed through many greedy hands. These books at Christie’s from the unknown consignor, on the other hand, had all been very well looked after; in fact it looked as if they had only recently been removed from the shelves of The RoyalLibrary, although this was not of course possible, for the books had been missing from our collections for more then thirty years. I could simply not get it out of my head that there must be a Danish connection behind the appearance of these books, although I had been told that the consignor was British, which was the only information we managed to get out of Christie’s concerning the identity of this mysterious person.

On my return to Copenhagen I had a meeting with Erland Kolding Nielsen that concluded in a notification of the theft to the police. A document was enclosed in which we demonstrated that all the books listed had been stolen from The RoyalLibrary. We were in the fortunate position that we could establish several pieces of evidence for each book to prove the ownership of The RoyalLibrary.

However, all was not plain sailing: we had difficulties. As the theft of the books had taken place more than ten years earlier, the case was statute-barred as a criminal act according to Danish practice. If we were to be able to pursue the case, we were advised to try it as a private lawsuit. This was not, of course, acceptable and we persisted by arguing that the case could at least be tried as a case of receiving stolen goods. It was really a few very dramatic hours for us, among other things we threatened to go public with the whole affair, but at last our points of view were accepted by the police authorities and on 23rd September the case was brought to court. The result was that the Danish authorities sent a rogatory commission to Scotland Yard in London in order to get the following information from Christie’s:

The identity of the consignor.

| - | Documentation of earlier business transactions with the same consignor. |

| - | Shipment-papers as documentation for shipments and shipping companies. |

| - | The names and addresses of buyers of books earlier delivered from the same consignor and sold by Christie’s. |

As the case began to develop, Kolding Nielsen decided to convert the paper catalogue of books missing from the Royal Library into a database, a project which was carried out within two months, on the pretext that the library had been given some extra funds which had to be used as soon as possible.

On 8th October I received a call from the police officer at the Danish police headquarters who was in charge of the case, and he informed me that the name of the consignor was Silke Albrecht. She was obviously a German lady from the small Bavarian town of Lindenberg. All agreements between Silke Albrecht and Christie’s had been made by telephone, and I was further informed that Silke Albrecht since 1998 had sold a considerable number of quite rare books at Christie’s. Every shipment of books had come from Lindenberg as a transport undertaken by a shipping company from Munich. This puzzled me. Normally stolen books look quite worn or more or less damaged but the sixteen books we had seen at Christie’s were all - as mentioned earlier - in very good condition, as if they had only recently been removed from the shelves in The RoyalLibrary, and I could not get the thought out of my mind that there must be some kind of Danish connection.

I began to search on the internet for the name Silke Albrecht, but only on Danish sites. The name Silke Albrecht is a quite common one in Germany but unusual in Denmark, and suddenly the name appeared on the MSN-Denmark site. Silke Albrecht was apparently a member of the marathon club of Elsinore, and had taken part in a quarter marathon. The next step was simply to find her address in the telephone book, which was quite easy for me. According to the telephone directory she lived in a flat in Elsinore. The Royal Library has maintained a copyright deposit since 1697, which means that the library receives almost all kinds of material printed in the kingdom of Denmark. It was therefore perfectly simple to check the Elsinore directory for the year 2002 and, according to this reference, Silke Albrecht lived in Steenwinkels Vej, but not alone. The entry in the directory showed that she was living with a man by the name of Thomas Møller-Kristensen. The surname Møller-Kristensen was quite familiar to me. It was that of a former colleague, Frede Møller-Kristensen, who had retired from tin 2000, and in January 2003 had died at his home in Espergærde, just south of Elsinore. He had been employed at the library between 1967 and 2000. From 1969 to 1987 he was the head of the Oriental Department but from 1987 he was employed as a research-librarian specialising in Indian philology, since he was an expert in the Pali language.

It seemed, however, that he had a few other interests or talents about which nobody in the Royal Library had been aware in due time. An informal chat with one of the staff-members from Frede Møller-Kristensen’s time established that Frede Møller-Kristensen had a son by the name of Thomas. At this moment, I remembered my own early years in the seventies in The Royal Library. At that time I was responsible for the stacks of the Danish Department, and I therefore became a member of the security board of the library in 1973. This special security board was established because the library had had the sad experience that quite a number of valuable and rare books from the foreign collections had disappeared from the shelves in mysterious ways, leaving no traces that could explain the disappearance. The police had been notified and discrete enquiries had been made for the stolen books from antiquarian booksellers in Denmark as well as abroad. The national librarian of that time had also notified his colleagues in Europe and in the United States of the thefts but none of these efforts paid any results at the time.

Identification of the thief

During the late 1970s the security board of the Royal Library developed a comprehensive system of security measures to prevent further damage occurring to the collections of the Royal Library, and from 1978 it could be said that the thefts did in fact cease. The case as such, however, remained unsolved, and no thief was caught. Several people were suspected and they were interrogated by the police, and this gave rise to an atmosphere of mutual suspicion in the institution for several years. Now at last on 8th October 2003 I was given the possibility to put a name and a face on the thief who for years had caused catastrophical damage both to the collections of the Royal Library and to all his contemporary colleagues. Again a moment to remember. A few other investigations were carried out in order to verify whether there really was a connection between Frede Møller-Kristensen and Thomas Møller-Kristensen. The names could be coincidental but these efforts confirmed that those two persons were father and son, and that Thomas had married Silke and furthermore, that they had been able to leave the modest flat in Elsinore and buy a house in the attractive village of Ålsgårde on the north coast of Sealand, not far from Elsinore and Espergærde, where Frede Møller-Kristensen had lived with his widow, Eva Møller-Kristensen, and where she was still living.

I tried to phone the police officer with whom we had been cooperating since September but he was busy, working on a nasty case of robbery and attempted murder. Two Cubanian refugees had that very same afternoon committed a robbery in a post office in Copenhagen and had shot and wounded a female civil servant from the post office. Instead I went to Erland Kolding Nielsen, and reported that we were now able to identify the thief from the seventies. Both of us were quite surprised. In his entire library life Frede Møller-Kristensen had given the impression of being a quiet, distrait, learned philologist, not exactly a skilled administrator but happy - too happy - for a pint of beer now and then, which had been the reason for his retirement from his position as department director in 1987 of the Oriental Department. In that way not only were we able to present a solution of the old matter of thefts from the Royal Library but suddenly the face of the perpetrator appeared before us, even though he was now dead and gone.

The next steps to be taken were to get search warrants, which is quite a complicated matter, as the law, of course, has to protect the security of the life and property of the citizens; in this case, however, there was strong evidence that a few citizens had behaved illegally, and the court decided that searches should take place at the homes of Frede Møller-Kristensen’s widow and of Silke Albrecht and Thomas Møller-Kristensen. Furthermore, it was decided that searches should also take place in Lindenberg and Munich in Germany, as the investigation had established that the books had in the first place been transported from Denmark to Lindenberg in Bavaria, and that from Lindenberg they were shipped to Christie’s in London by an art shipping company in Munich, which meant that this shipping company had also to be searched. Since Germany is a federal state, it took time to get hold of the search warrants from the Bavarian and federal authorities, but at the end of October 2003 the necessary paperwork had been done. In the meantime the Danish police officer and I paid a visit to Scotland Yard in order to get further documentation of the transactions between Christie’s and Silke Albrecht, and we succeeded in getting hold of copies of their accounts and sales which Christie’s had made on behalf of Silke Albrecht, whom Christie’s thought to be living in Lindenberg. The address of Silke Albrecht’s mother, Theresia Albrecht had been used as a cover by Silke Albrecht. The conclusion was that Silke Albrecht had sold or tried to sell 36 books at Christie’s for 415,540 GBP.

The 5th November 2003 was chosen as the day on which the searches in both Denmark and Germany should take place. Antiquarian books are normally not a topic for Danish police officers, and this case seemed to be quite extraordinary, as far as it could be judged from the sixteen rare books found at Christie’s. As the liaison officer of the Royal Library I was asked to point out another specialist who could assist the police in identifying books as the property of the Royal Library. I chose the librarian who had been the head of the revision group of our collections, as no one in the library had seen or had in her hands as many rare books as she had and this also meant that she was well aware of the diversity of our collections. And last but not least: she was a person of whom I knew that she could not in any way be connected with the thief or the thefts. Though we now knew the identity of the perpetrator, we did not know whether he had had connections in the library of which we were unaware. It was therefore extremely important that only a very few persons in the library should know what was going on. It was decided that this librarian, Susanne Budde, should take part in the searches in Denmark, and that I should assist in Germany. The German authorities had seemed a little reluctant to take the matter as seriously as we did in Denmark.

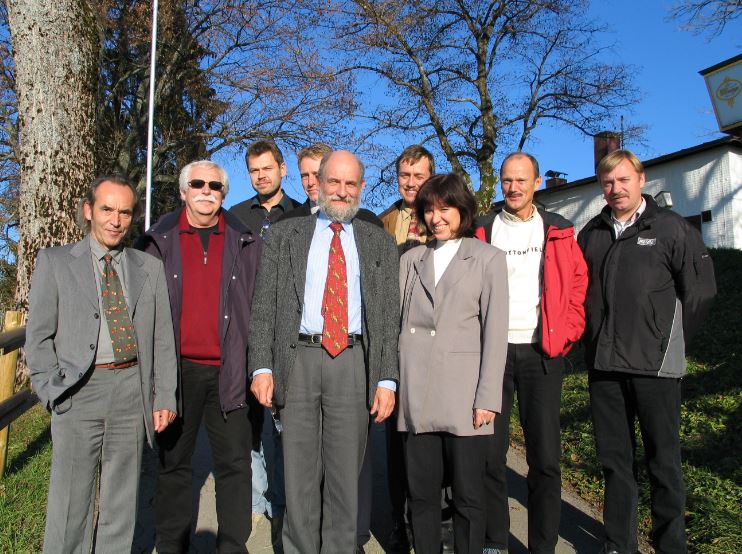

On 4th November we, i.e. two Danish police officers from Copenhagen, two Danish police liaison officers from Bundeskriminalamt in Wiesbaden, two Bundeskriminalamt-people from Munich and two representatives from the Bavarian police in Lindenberg and I had a planning-meeting at Bundeskriminalamt in Munich, at which I was asked to give an account of the case from the perspective of The RoyalLibrary. It was decided that the searches in Denmark should start at 5 o’clock in the morning but the German police insisted on waiting to start until 10 o’clock, which caused some difficulties for the Danish police, as it would be necessary to keep each of the suspected persons in Denmark isolated for some hours to prevent them from warning each other. In the end this was an advantage because we knew the result in Denmark before the action in Lindenberg and Munich took place.

Figure 2: The ransacking team from Germany.

Already at breakfast at the hotel in Lindau, an idyllic town situated on a small peninsula in Lake Constance, which was the basis for the German operation, only a few miles away from Lindenberg, we knew that a total of about 1,500 books had been found in the home of Frede Møller-Kristensen’s widow. Five other quite rare books were found at Silke Albrecht and Thomas Møller-Kristensen’s home in Ålsgårde. These five volumes had been ready for sale, i.e. all the traces which could connect them with the Royal Library had been carefully removed. In Lindenberg at the home of Silke Albrecht’s mother, the result of the search was apparently quite modest: only four books, of which two had been returned from Christie’s as unsold. However, the most important result was that the police found some accounts of books which had been shipped to London and some quite compromising letters from Silke Albrecht to her mother that proved that mother and daughter had cooperated in this business, and Theresia Albrecht was taken to the police station in Lindenberg, where she was questioned for two hours about her knowledge and what profit she had made from her daughter’s activities. At 11 o’clock the searches were concluded. The search at the shipping company was quite successful, as were some bank investigations into a few accounts of Silke Albrecht’s in Germany. I phoned Erland Kolding Nielsen to inform him about the results of the actions in Denmark and Germany. He was quite amazed at this result! As he already on the 31st October was confidentially informed by the Copenhagen police about the coming search and therefore had arranged an appointment with the Minister of Cultural Affairs for the afternoon of the 5th November, he was able to inform him and the Ministry personally about this surprising development, i.e. before the press eventually got hold of the story. The Minister of Justice was at the same time informed by the Copenhagen police commissioner, as it was considered to be a very important case due to the value of the missing books.

In Denmark, Møller-Kristensen’s widow, her son and daughter-in-law were taken to a preliminary examination and imprisoned, where they were kept in isolation with no possibility of making contacts outside the prison with the exception of their defending counsel. This form of imprisonment has been much discussed in recent years because it can be psychologically damaging for those involved. It is employed, however, in cases where the judge in charge of the preliminary examination considers that the prisoner under remand might otherwise be able to hinder the solving of the case. It is probably also employed to encourage the prisoner to confess to the offence in question. The following day, an Irish friend of the family was also imprisoned, since he had confessed that he had transported books to the USA and that his sister in New York had helped him to sell these books at the auction house Swann’s Galleries.

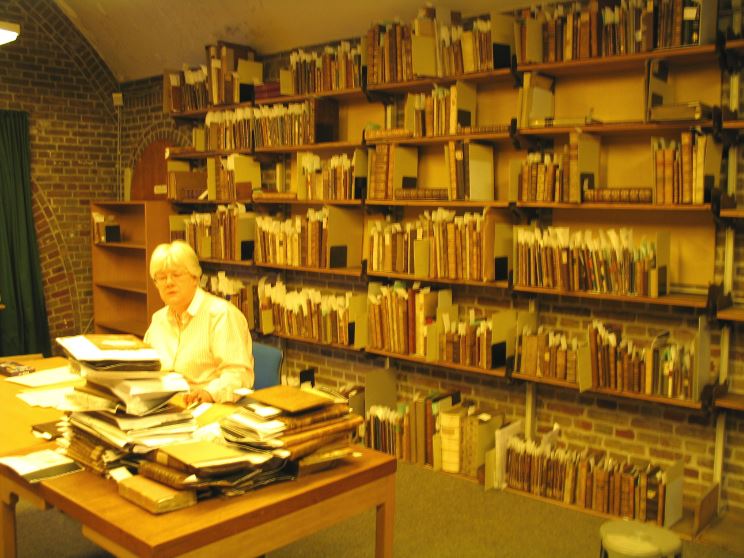

From November 2003 until 1st February 2004 all the books which had been found in Espergærde at the house of Frede Møller-Kristensen’s widow were registered and described in a way which could convince the court that all these books were the property of the Royal Library. This extraordinary task was too complicated for the police to carry out, and I was asked whether the Royal Library could place specialists at the disposal of the police to deal with this. I gathered together a small team of rare books librarians to do this work, which had to be done in secret in order not to confuse what remained to be cleared up of this matter. It was extremely important that the press should not get any hint of what was going on. This meant that all the books were taken to the police headquarters in Copenhagen and two offices were put at our disposal to carry out discretely the work which had to be done to prepare the case for the court. First of all it was necessary to list all the 1,665 books found on a special list for the court. Each book received a number for identification on a slip and on the list in which it was catalogued: Author, title and imprint, as well as a brief description of any characteristic features of each book, provenance, rareness, owner marks etc, as well as an indication of the value.

Figure 3: Registration of the books at the police head quarter in Copenhagen.

Two photocopies were taken of the title page and the number of each book was written on these copies. One of these was placed in the book, the other was taken to the Royal Library, where two librarians checked shelf mark, author, title and imprint in the database of missing books and marked each entry for the books that had been found with a special code. These two colleagues were only informed that the old case had been solved but they were not told the identity of the criminals. As for the books, they were packed successively in boxes and transferred to one of the strong rooms in the Royal Library day for day, as there was not sufficient capacity in the storerooms for stolen property in the police headquarters. This did not mean that the books were now considered to be the property of the Royal Library but in a way the Royal Library was acting on behalf of the police and the court.

Every late afternoon from November 2003 until February 2004, on my return from the daily work in the police headquarters I gave an account of our various findings for Kolding Nielsen in his office. Besides this topic of conversation, the standing agenda for our meetings was as follows:

Special rare books regained during the day. Among these was Thomas More’s Utopia printed in Basel 1517. Originally the Royal Library had also had the Louvain edition [1516] which had last been seen in an exhibition at the Royal Library in the summer of 1969. However Silke Albrecht had succeeded in selling this edition at Christie’s on 7th June 2000, the profit to her and her family had been 140,000 GBP.

| - | Discussions, i. e. the development of theories as to the possible motives of Frede Møller-Kristensen. |

| - | Various analyses in an attempt to date the beginning of Frede Møller-Kristensen’s thefts. |

As for the last subject, it was the retrieval of two Danish books on astronomy which gave us an opening, for the catalogue of astronomy in the Danish Department had been removed from a stack in the main building of the Royal Library to one situated at another address in Copenhagen, to which Frede Møller-Kristensen had no access. The collection of astronomy had been removed 1968-69, as far as it could be established. As Frede Møller-Kristensen obtained his position as a research-librarian in 1967 and was already promoted to the post of department director in 1969, it was our theory that he must have started his criminal activities almost from his very first day in The RoyalLibrary, which was both a fascinating and a frightening thought. I must confess that Kolding Nielsen and I never managed to bring our discussion of this subject to its final conclusion. This is not because we were in disagreement but the problem continued to puzzle us. We still discuss this subject from time to time. The finding of 9 atlases which disappeared on Saturday the 13th October 1975 was another case we discussed very intensely. The atlases had been used in the reading-room of the Department of Maps on Friday 12th October 1975 by a Norwegian scholar, and when they were required again on Monday 15th October, the staff of the Map Department was unable to find them. The case was reported to the police, and inquiries were made via Interpol.

In May 1976 one of the missing atlases apparently turned up in Paris. One of our specialists from the Map Department immediately went to Paris, escorted by a police officer from Copenhagen. She could have sworn that the copy of the atlas which was shown to her was identical with the one which had been stolen from the Royal Library, but this copy showed no evidence which could prove that was the correct owner. The conclusion of this case was in the negative, which was quite frustrating at that time because we were then still convinced that this copy originated from the Royal Library. We were quite wrong, however: all the 9 volumes of atlases were found in the house of Frede Møller-Kristensen’s widow on the 5th November 2003. This case proves how difficult it can be to identify stolen books when they have once reached the world outside the library. During the search at the house of Frede Møller-Kristensen’s widow a complete set of tools for binding and book restoration was found. In a way, this discovery brought the explanation of why Frede Møller-Kristensen had always taken such a great interest in the care, restoration and preservation of the collections of the Oriental Department. It had until those remarkable days in the autumn of 2003 always been considered as ‘good professional custodianship’. Now, his enthusiastic engagement in this particular field of the work of the library revealed that Frede Møller-Kristensen’s motives had been of a quite different nature. His real intention had been to find out how he could best remove stamps, shelf marks and other characteristics, which could link a particular copy of a book with the Royal Library, a theme which Kolding Nielsen and I also discussed very intensely.

We succeeded in keeping the whole matter secret until 9th December 2003. On that date the Irishman had been in court and his solicitor had demanded that he should be set free. The court had not approved this, however, and instantly the press got wind of the whole matter. I do not claim that the solicitor was the source of this particular press leak, for that would have been illegal, as her client was technically in solitary confinement and this meant that it was forbidden for the name of the person concerned or the case to be revealed to the press or anyone else. This was of course a new difficulty in our path, which caused some delays, as both the police and the library had to answer many more or less futile questions. From that day on, the attention of the media, and soon also of the political world, was on the case. This was a new aspect of this matter, not exactly surprising, but it was a new situation and it meant that Kolding Nielsen had to publish an article about the case in the Danish newspaper Jyllands Posten: “The Anatomy of Book Thefts”. However, it did not help much: The story had developed its own dynamic in the media and we had to compile a comprehensive report for the Ministry of Cultural Affairs, explaining both the present state of affairs and its historical dimension, since the media and a few politicians mixed past and present in a way which made the very clearing up of the affair look like a scandal. I shall not waste more time on these trivialities. In May 2004 all the four perpetrators were sentenced to prison. The 69-year-old widow was to serve two years in prison, her son three years, and both the Irishman and the daughter-in-law one-and-a-half years each. The facts were taken into consideration that Silke Albrecht and Thomas Møller-Kristensen had a two-year-old child and that the widow was almost 70 years old.

Figure 4: The books recovered.

The security perspectives of this matter

Quite apart from those security measures which are designed to prevent books, manuscripts and other valuable items which old libraries have in their possession from being stolen or disappearing in unaccountable ways, it is very difficult to regain items once they have disappeared. In the following I shall try to list some of the most significant experiences and difficulties which have to be dealt with in such cases.

| 1. | It is very difficult to claim the ownership of stolen books when they have once reached the market, i.e. auction houses or antiquarian book dealers. Stamps, marks or other signs of ownership have very often been removed, which means that auction houses, antiquarian book dealers or other buyers have normally bought a stolen item in good faith. |

| 2. | It is very difficult for a library to cope with a matter of this kind. You cannot go public because this will simply ruin all possibilities for the police and the library to investigate and clear up the matter. All experience shows that the press and the politicians simply use cases like the present one for their own purposes. They very often have their own agenda: the newspapers and the media world want to sell scandals and sensations, the politicians aim to sharpen their profile as politicians who can be remembered and elected again another time. |

| 3. | There have been two victims in the present case: the Royal Library which has had its books stolen and the auction companies who have been cheated. Stamps, marks and other evidence which could relate a particular book to the Royal Library had been carefully removed from those books which Frede Møller-Kristensen had prepared for sale. He had a complete restoration workshop in the basement of his house, as well as a set of quite professional bookbinding-tools, and he knew how to use his tools. |

| 4. | The international legislation concerning the illegal traffic in cultural property is, to put it diplomatically, expressed too weakly or vaguely to play any important role in the international struggle to find stolen books and restore them to their legal owners. |

| 5. | The public, legal control with auction houses, the antique trade and antiquarian book dealers is far too weak. In the case in question it delayed the solution of the matter that Christie’s would only reveal the identity of the consignor after the presentation of a court order from the British police. In cases like this one it might be a realistic possibility that the stolen goods would be handed back to the consignor if the auctioneer or the antiquarian book dealer becomes suspicious. Situations like that leave the library and the police without any chance of regaining stolen items. |

| 6. | It will be necessary to create closer cooperation between the antiquarian world and the libraries but it will also be a basic condition that the antiquarian book dealers and the auction houses become more open to the library world. |

| 7. | Libraries are public institutions and accessible to any citizen, while auction houses are private enterprises, whose only obligation is to earn money for the benefit of the houses and those consignors who make use of the services which those institutions provide. |

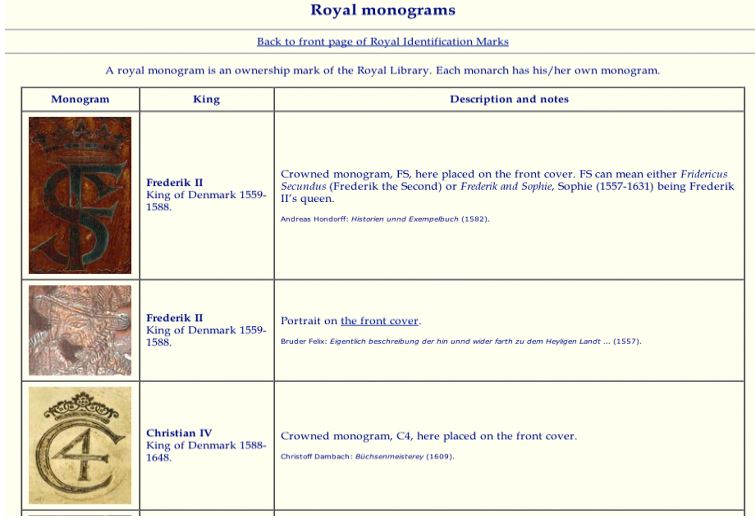

As mentioned above, in the present case there were two victims: Christie’s and The Royal Library. You might ask in what way do the libraries mark or describe their precious material so that a second part, for example an auction house, has a possibility to identify rare books originating from a library? Up to now the only public registers of library books have been the library catalogues. The purpose of a library catalogue is firstly to register which books or other documents the library has in its possession and secondly to make those documents accessible. This means that the descriptions of the books in library catalogues are very often very modest. Many library catalogues are simply short title catalogues which in a practical manner make it possible to verify and locate the books on the shelves. On the other hand, an auction catalogue does not normally reveal traces which could connect a particular copy of a book with a certain library. The intention behind auction catalogues is to promote a sale and this means that the characteristics mentioned are designed to make a particular book attractive for a collector or an investigator, which is the reason why those aspects of the history of the volume which deal with rarity or value are very often emphasized. An owner mark or a certain name or a stamp which could mean a lot for a librarian with respect to the provenance of the book would often not be mentioned or only described in lapidary style: unidentified name, or provenance: “From a gentleman’s property.” This makes it quite difficult for a library to identify a particular missing book as that particular copy which has been stolen from the library. In searching for stolen books details of author, title etc. are not particularly useful for the police. When you report to a police officer the theft of a rare book, his first question will be: What does it look like? What should we look for? In such cases the librarian will most likely not be able to give any sensible answer. The solving of the thefts from the seventies and the new digital technology made it possible for us to create a new instrument, Royal Identification Marks. It is a picture gallery of characteristic bindings, stamps, owner-marks and shelf marks in the Royal Library which makes it possible to link a particular book with the library.

Figure 5: An example from Royal Identification Marks.

We sincerely hope that this new instrument will also be useful in a more traditional kind of history of the book.

Related articles

Kolding Nielsen, Erland: “Bogtyveriernes anatomi.” Kulturkronik i Jyllands Posten 30.12.2003.

Kolding Nielsen, Erland [et al.]: Opklaringen af bogtyverierne på Det Kongelige Bibliotek i 1970’erne. Redegørelse til Kulturministeriet. Det Kongelige Bibliotek, 2006. http://www2.kb.dk/kb/missingbooks//Baggrund/opklaring-bogtyverierne.pdf

Hansen, Torben; detective sergeant, Copenhagen Police, Dep. C.: “Tyveri af bøger fra Det Kongelige Bibliotek.” In: Nordisk Kriminalreportage, 2006, pp. 79 – 92.

Düring Jørgensen, Jesper: “Report on a Theft of Books, a Non-Fiction Detective Story.” Care and Conservation of Manuscripts, vol. 9. Cph.: Museum Tusculanum Press, 2006, pp. 113 – 125.

Düring Jørgensen, Jesper: “Om bøger, bogtyve og sikring på Det Kongelige Bibliotek”, Nordisk Tidsskrift för Bok och Bibliotekshistoria, 2007. [In print]

Web sites referred to in the text

Royal Identification Marks. http://www2.kb.dk/kb/missingbooks//marks/index.htm

Royal Library: National Library - Copenhagen University Library - The Black Diamond. http://www.kb.dk/en/index.html

Note

| [1] |

This article is a revised and extended version of “Report on a theft of books, a non-fiction detective story” published 2006 in Care and Conservation of Manuscripts, vol. 9. Cph.: Museum Tusculanum Press, 2006, pp. 113 – 125.

|