'To clean the face, wash behind the ears and brush the teeth'. The project to conserve the Norwegian written heritage,

2001-04 and its results.

INTRODUCTION

At the National Library of Norway two major projects, a conservation project and a card conversion project were planned and will by June 2004 be partly completed. This article presents the projects, with the main emphasis on the conservation project, which was my responsibility.

History: buildings

In 1990 it was decided that the national collections of the University of Oslo Library were to be moved to the newly established

National Library of Norway. The old University Library moved to a new building on the campus of Oslo University. The National

Library began its work with two divisions: at Mo i Rana in northern Norway work began in 1990, in Oslo work began in 1999

in the old library building of the University Library. For the Oslo division it was decided that this building from 1914,

with two wings added to it in 1932 and 1940, were to undergo extensive modernization and have new, underground stacks built

on site. Planning for new, underground stacks and the rehabilitation of the old building began in 1997. However, the political

situation made it difficult to know when the plans could materialize. By 2002 the plans began to become reality.As for the underground stacks, they were to be constructed in three levels below the levels of the old building. The stacks should be mobile compactus shelves with special compartments for the special material and will be completed in 2004.

As for the old library building where the stacks formed part of the structure of the two wings, they were going to be torn down from the inside, leaving the exterior as it was, but with a completely new interior. The main building will undergo less extensive rehabilitation because The Directory for Cultural Heritage decided that most of the interior on two floors should be kept intact. The rehabilitation project began in 2003 and will be completed by June 2005.

History: temporary and permanent moves

Obviously the library had to move out whilst new stacks and rehabilitation took place, but for a long time nobody knew just

what to plan for and when. Problems connected with a) finding a suitable place to move 35 km of books and approximately 160

people; b) moving all books at one time or leave one wing of books to be moved at a later stage; and c) the expenses incurred

by moving, and the choice between more suitable, expensive premises and cheap ones made the then National Librarian and those

she consulted with vacillate for some time. Finally in late March 2003 the Ministry accepted the rehabilitation plans, in

April the all-clear for the moving of staff and most of the material in the special collections to premises near the old address

was given, and the actual moving began in May 2003. At the same time the book collections were to be moved to a huge warehouse

in the outskirts of Oslo. The library was ordered to have the building empty by August 1st, 2003. The plans and the actual

move were made at top speed.However, it was very difficult to plan the shelving in detail because, in order to save money, the National Librarian ordered us to reuse shelves from Mo i Rana - shelves that were not ready to be moved by the time we were to begin our exodus. In addition the demolition of the old library stacks began before we had moved out, and our best lift was demolished in this process, leaving us with books on two floors without a lift. Other problems that arose will not be mentioned, since this is not a story of a move but of a project.

One implication of the rehabilitation of the building was that our old card catalogue for the general public, occupying a room of at least 200 m2, had to be discarded. This union catalogue for books at the University Library and at the National Library, containing information about the holdings of both libraries, was the only way to retrieve information about the foreign material left at the National Library. Consequently it became imperative to recatalogue the foreign material.

Most of the National Library's book collections will move back into new stacks in June - August 2004, whereas the staff and all the special collections will move to the rehabilitated library in June 2005.

PROJECTS AND SCOPE

In 1998 the Oslo division began an inquiry into the physical conditions of the national and special collections in order to be prepared for all events concerned with the rehabilitation of the old library building. The conclusions drawn from the inquiry led to two momentous decisions, costly in manpower and resources, but very important for a possible success of this newly established symbol of the nation: The National Library. The heading for this project was: "New National Library, Oslo".

The project comprised two main tasks:

| • | The construction of underground stacks and the rehabilitation of the old library building. |

| • | The conservation and conversion of our national written heritage. Under this umbrella two projects were designed: one for the conservation of material and one for the conversion of the card catalogues. |

The first project was based on the decision that all collections of national importance should be thoroughly cleaned and rewrapped. This amounted to approximately 3.5 million single items. At the basis of the project lay an exhaustive investigation of:

| • | checking out how much time one operation would take; |

| • | what quantities of acid-free wrapping paper, casks and boxes were needed; |

| • | how many conservators and how many extra staff with what kind of qualifications should be employed in order to complete the tasks. |

Special tests were undertaken for each special collection and for each operation.

The scope of the second project was to convert 600.000 catalogue cards to digital form through the recataloguing of the actual items. This implied that the library would need over a period of four years 60 extra man-years. Here we investigated:

| • | should the conversion take place from the card catalogues or from the shelves; |

| • | to what extent did the card catalogue cover the actual holdings; |

| • | should trained librarians be used for all operations, and what figures should a man-year of conversion produce. |

It was decided to catalogue the Norwegian books from scratch because a time study demonstrated that this was less time-consuming, and because the catalogues did not reflect our actual holdings.

Finally, in the year 2000 we presented to the Government, through the Ministry of Church and Culture, a plan in two stages, asking for extra finances for hiring extra personnel and for conservation material. Stage one had as its aim to have all the legal deposit material cleaned reboxed and recatalogued by the summer of 2004 when the new stacks were completed. Stage two had as its aim to have all the special material rewrapped and reboxed and all the special catalogues converted by the time we could move back to the rehabilitated building at the centre of town in 2005.

ARGUMENTS FOR THE PROJECTS

There were several good arguments for these two projects. The first project concerned books that were so dirty that some of our staff had got asthma and eczema from working in the stacks. The dust accumulated during the years in a heavily trafficked street was so thick that it would clog the air-condition and air-temperature control machinery that was to come as part of the new stacks. All wrapping had been done with acid paper, papers were kept together with rubber bands that had rotted away decades ago, old boxes were falling apart etc. The second project was related to the ideas behind the establishment of The National Library. Both in the Parliamentary debates and in the Governmental documents related to the establishment of a new national institution, it had been argued that to set up a division of a national library in the north would demonstrate to the nation that this was going to be a modern institution, based on the most innovative digital concepts. Digitalisation would do away with barriers such as distance, and whether collections were placed in the north or in Oslo would no longer matter to the audience. The National Library was going to be a modern beacon light for the whole country, in the forefront of the digital development.

The projects had as overall ambition for the collections of national importance:

| • | to improve the physical conditions of collections, |

| • | to improve the Library's knowledge of its holdings, |

| • | to improve the retrieval system for the collections, |

| • | to further the Nation's knowledge of its written heritage. |

In other words, the projects should improve the condition of the collections, make them more accessible and more known to the nation in order to comply with the Norwegian vision as expressed in Parliament that every citizen should have access to all information, no matter if he lived centrally or in the periphery.

When the annual budgetary announcement from the Ministry came in January 2001, it was evident that the application to the Ministry for this extra funding had been turned down. The plan as such was accepted by the Ministry, but without any extra financing.

SCOPE ONCE MORE

Evidently the projects had to be reduced in scope and the library had to seek other solutions for its problems. In desperation, staff from the department of national and special collections commenced work on the plans drawn up for a trial period, each employee spending from 1 - 10 hours a week on the project. Within a short time we understood that 'to muck out our Aegean stables would be a Sisyphean task' beyond our means.

The library concluded that the only possible solution was to close the library for two years, from 2001 to 2003, allowing all the staff to conserve and convert. A reduced plan was outlined. The scope was reduced to 67 man-years for both projects. Within the conservation project certain tasks were given priority before others and within the conversion project, the emphasis was placed on eliminating the main card catalogue of Norwegian printed matter. The Ministry however, after internal discussion and external publicity, including newspaper debates, did not grant us the permission to close the library. Instead, during the autumn of 2001 they came up with added financial support, plus the permission to reduce our opening hours. During the next year this financial augmentation was incorporated into the annual budget of the National Library.

It seems appropriate at this point to say that whereas an institution hardly ever gets as much money as is applied for, the ministerial grants, when they came, were substantial. Most of our figures for material such as rewrapping, boxes etc. were accepted with the provision that they had to be left to an EU tender. We had, after all, at the first application asked for what would amount to approximately 16 million NKr. just for wrapping material and equipment for the conservation project. The sums finally agreed upon were approximately 9 million, and the sum actually spent appears to be even less than 9 million NKr. As for extra personnel, the Ministry felt that the library could reallocate more of our staff than we had originally envisaged, but granted us money for 17 extra man-years for both projects.

The library changed its list of priorities and gave low priority to certain tasks in order to be able to reallocate staff. The special collections closed its doors to the public one day a week and the library only opened in the mornings at 11 o'clock. An internal process was initiated, where the library did its best to make all who participated feel that they were taking part in a process that would transmogrify the library from 'the old run-down lady of the University Library' into 'the informative, good looking and mature woman of the National Library'. We all set to work.

THE PROJECTS SUCH AS THEY BECAME

After the reductions, the conservation project implied:

A1) The periodical task: arranging the non-bound periodicals, previously kept together with strings or in dilapidated boxes, into new acid-free stable boxes that could withstand the movement back and forth in the planned new mobile compactus stacks;

A2) The periodical task: reshuffling the periodicals, i.a. a plan to reshelf and renumber the national periodical holdings that for years had been placed wherever space was available. Quite a few of the more frequently used periodicals had even been integrated into the legal deposit book section. In addition the periodical section decided to start on a completely new shelf system for the approximately 12.000 national periodicals from Jan. 1st, 2003.

B) The special collections task: rewrapping in acid free paper material such as manuscripts, letters, photos, maps, posters, musical manuscripts etc. in our special collections. Every item of important material was rewrapped, each item of our photo collection was placed in an acid-free envelope, a polythen bag or a polyester pocket, and for extremely large formats and extremely fragile items, a programme for digitising items was drawn up. All deposita and all non-opened material was also to be gone through.

C1) The legal deposit task: vacuum cleaning all the legal deposit book material from before 1960 in order to remove as much soot and old dust as possible.

C2) The legal deposit task: exchanging old acid wrappings in the legal deposit collection with new wrappings made of sustainable, acid free paper or new boxes.

Since part C in this decision implied the handling of every single item in the collections of legal deposit books, we also decided to compare the actual items on the shelves with the shelf lists, to make a list of missing items, to note down every book that needed repair with a grading system of three levels (level a: repair ½ hour; level b: repair more time consuming; level c: repair so costly that rebuying from antiquaries was attempted), to box/rebox all unbound copies (in Norway the responsibility for the legal deposit copy doesn't rest with the publisher but with the printers, hence quite a lot of the books are in sheets).

The conversion project had had as its aim to do away with both the main card catalogue and the catalogues for the special collections. A card-catalogue-less library was our vision. Up to 2004 the focus would be on the digitisation of all the catalogue information on the legal deposit material. In addition some foreign material had to be recatalogued because the old card catalogue was discarded.

INFORMATION

Two separate web pages were created, one for internal use and one for external information. The external web page encompasses the total project, i.e. the building plans and the conservation and the conversion projects. The web pages also include information on interesting 'nuggets' from our collections. Whenever we came across interesting material that we felt deserved to become better known, it was digitised for the external web page. We also described in detail what conservation measures had been taken, with a picture of 'before' and 'after'. Since the library had reduced its opening hours, such information was one way of justifying this decision and at the same time keeps the audience informed about activities in the library. This was rather effective. Various radio channels came several times to interview us about the activities and the newspapers also followed up on information they found of interest. The internal web page contained information on the project plans, progress made, reports, information about the participants etc. One internal by-product of the projects was that we found items within our collections that we had previously not been aware of.

FINANCES AND EMPLOYMENT

To sum up the downscaling of the plans that took place: the goal had been to convert 600.000 cards to digital information, to clean approximately 16.000 shelf meters of material, rewrap approximately 550. 000 items in the special collections, and make use of approximately 37.000 new boxes. The reduced estimates that we sent the Ministry in the summer of 2001 were based on 67 man-years of work and wrapping material for approximately 12 million NKr. After further reductions and tenders the first phase of the projects was dimensioned to 56 man-years of work and about 9 million NKr. in expenditure for wrapping material. This involved employing 17 new people and reallocating what amounted to ten permanent positions for the time of the projects. With the reallocation of our own staff and the added temporary personnel of 17, including two positions as leader of projects, the work could begin in the autumn of 2001.

STAFF PARTICIPATION

The staff at the Department of National and Special Collections have at all time been heavily involved in the project. We began by having a brainstorming meeting where all suggestions for the project were noted down and discussed. I followed this up with an interview with all the staff to find out where the individual employee felt he/she could contribute best in the project. Some of the staff preferred working within the conversion project, whereas quite a few accepted doing menial chores, such as vacuum cleaning once a week. My problem then was to decide what tasks should be downgraded during this period. Personally I argued for less work put into the annual gathering of statistics (which in my opinion is needlessly detailed and takes up an extraordinary amount of time). Unfortunately this suggestion was not accepted, and we had to make do with various makeshift-downgrading arrangements. Within the Department of National and Special Collections, every physically able member agreed to use 20% of his/her time to the project. Most of those who for health reasons could not participate in the conservation project were reallocated to the conversion project or given other tasks.

For the staff at the periodical section it was felt that the problems there would be so confusing to the uninitiated that the section was better off coping all alone. One half man-year plus some temporary aid was reallocated to the project. We have also tried to find ways to reduce their other work, but since they work with legal deposit matter, this has not been easy.

For the staff at the special collections, the project was a golden-sent opportunity to thoroughly examine our collections, revise them, clean them and clear out certain deposits that had remained in the library for more than 100 years etc. There was no lack of enthusiasm for this project, neither within the hired temporary personnel. We had deliberately employed some highly qualified people to work part time within fields that they had already specialised in during their thesis work.

The national legal deposit collection was perhaps the field where it was most difficult to drum up enthusiasm. The sheer dirt of the material made the work very unattractive. Also the legal deposit is nobody's and everybody's responsibility. One further reason may be that one should be thoroughly familiar with both Norwegian culture and with all the vagaries of the collections to see the worth in what we did.

All had to use special protective clothing, most people wore masks whilst vacuum cleaning, and some even showed tendencies to develop asthma or eczema during the work. To face one shelf meter with perhaps 100 items that needed dusting, removal of dirty old wrapping, rewrapping, checking the shelf list and noting down lacunae, sometimes represented an intolerable mental challenge, especially since we, at the temporary site, had to work in a cramped and stuffy room.

Nevertheless, even though the dirt was a demotivating element and one had to be fond of the collections to undertake such work; I would argue that this part of the project was most needed and most useful. We did at certain times get some help from other departments, such as one person preparing all the boxes that were to be used, but most of the job was done by our permanent staff plus the temporary personnel.

During the 2-3 years that the project has been going on, I have interviewed all the staff at my department (approximately 40) twice, once at the initiation of the project and once just before we started our first move to a temporary site. It is extremely satisfying to be able to report that most of the staff has at all times been supportive of the ideas behind the project and have actively participated in the projects.

ENCOURAGEMENT, ENDURANCE & INCITEMENT INITIATIVES

One of the first activities undertaken, both for all newcomers to the project and for the permanent staff involved in the project, was to arrange a course in how to handle paper material, what aspects of conservation were important, where to be extra careful, special health concerns, what rewrapping material had been ordered and how it was supposed to be used etc. Mainly our own conservators gave the course. Our conservators also gave later newcomers a crash course introduction along the same lines. In addition, a seminar in conservation and paper history with invited guest speakers was held for all interested. Later on two topics were selected for special lecture courses, one a course in Gothic script, the other an introduction to book history. Both courses proved very popular, and were attended also by staff not assigned to the projects.

SPECIAL PROBLEMS

It soon became evident that the project, even in its scaled-down form, was overambitious, and had to be readjusted.

| • | For the periodicals readjustment was impossible because stable boxes are a sine qua non in mobile stacks. We know that mobile stacks will be a reality; therefore the reboxing must be completed by the time most of the periodicals will be moved to new stacks in 2004. However, lack of space at our temporary sites makes it impossible to complete the final reshelving and renumbering of the periodicals before the move to permanent stacks. Even though we know the logistics will be formidable, we have decided to fit one part of the project into the tender for the moving of books, i.e. to set aside time for our staff to rearrange the periodicals during the actual moving process and in the time before the next move. |

| • | In the special collections we had to reduce the level of rewrapping and focus on the most fragile and more frequently used material. Decisions on this have had to be made ad hoc, relying on individual assessments. In the time between the return to new stacks and the final move of the special collections, i.e. between June 2004 and June 2005, we hope to make further progress here. |

| • | As for the most comprehensive part of the project - to bring our legal deposit collection into as perfect a condition as possible, to detect all lacunae in the numerus currens shelf-list and try to identify all missing numbers, proved too time-consuming. We had to fall back on noting down identified, missing objects and compile lists for further work after the project is terminated. Further, we decided that the most thorough cleaning and checking would be applied to books before 1960. In other words, vacuum-cleaning will also form part of the moving tender. |

WHERE WE ARE, MARCH 2004

As mentioned, for the periodical task of the project, problems with space in our temporary building have made it impossible to have a proper sequence of the periodicals made before we move to our new premises. However, most periodicals are now in solid boxes, and a new sequence, starting from 2003, has been initiated.

The special collections task is still in progress. Most of the resources allocated to vacuum-cleaning have been reallocated to the special collections. As mentioned, the special collections will only move back to the old, renovated building and the new stacks once we all move back in 2005. In this part of the project we have found treasures that we did not know we had, and that had, at one time or another, been placed in a box and forgotten. Daguerreotypes and old prints that had been hidden under posters, more than 2000 theatre- and circus posters - so fragile that we hardly could touch them but containing large amounts of local information about what entertainment was offered in rural areas more than 100 years ago -, letters from well-known authors, hidden within boxes with unregistered correspondence, just to mention a few.

The legal deposit task completed before time. At the end of February 2004 the conservation project was completed as for part C. This is especially impressive for three reasons:

| • | There was a stop in the work during almost three months in 2003 when the library moved from the old building to the two temporary sites. All the temporary staff, in both the conservation and the conversing projects, was then heavily involved in the moving process. |

| • | With the books at a separate place the projects got serious problems with the logistics of moving books temporarily back and forth for conservation and conversion. This time-consuming process involved more than one full time position, and was certainly not part of the original plan. The site for books does not offer facilities for either of the projects. |

| • | The temporary moves were so costly that the Oslo branch risked having a deficit in its budget. By September 2003 The Board of the National Library therefore decided on an appointments freeze in Oslo. |

Nevertheless, we could celebrate the completion of one part and take stock of our achievement. We are now able to face the move back to the old premise in a new, underground building with equanimity.

THE RESULTS FOR THE LEGAL DEPOSIT COLLECTION

For the legal deposit task we now have a solid foundation on which to assess our legal deposit, we know what material is lost and we can outline a policy for filling in lacunae. We know how large a percentage of the books need repair and conservation. If the library or the Ministry wants, we can make concrete plans based on solid figures. We are pleased to think that we in the autumn of 2004 can offer our public fairly clean (as clean as vacuum cleaning can make a book) and well-preserved material for study. And we are in the privileged situation of having a national legal deposit collection whose condition has been thoroughly surveyed and registered.

When the conversion part is completed we will also be able to find out when we have two copies of a book, and we may, if we so wish, discharge the damaged one in order to establish as perfect a legal deposit collection as possible, or send the second copy to the branch in Mo i Rana. (If two copies exist, the Rana branch is to serve as the lending library for legal deposit books.) The conservators have a list of damaged books to work from. Our hope is to link that list to a system that automatically activates a conservation need if a book is in demand. From this list and from figures on demand we may decide whether a book should be conserved, whether it should be digitised, or whether we should attempt to buy a 'new' copy from an antiquarian.

A further benefit from this exhaustive examination of the legal deposit is that we have 'purified' our legal deposit collection. Since this historical collection (books from 1643) has never been controlled or revised since the 1880s, it should not surprise anybody that within it are layers of history. At one time albums with photographs were placed within the collection, so were small ephemera, quite a lot of them bundled together and wrapped in brown paper under one heading, with little or no reference in the catalogue. We found items such as beautiful posters for boxes of sardines from 1890s, theatre programmes nobody knew we had, photo albums from historical periods, just to mention a few. All this non-book material (estimated to 2-3.000 items) went from the legal deposit collection to the various special collections, or it remained within the legal deposit collection, but reboxed and with a note in the computerized catalogue for ephemera. We also found large scrapbook collections with paper clippings from different people or different periods. These were given a meaning-bearing title and a signature in the database. Such material should be of great interest to the specialist scholar since it now is possible to retrieve the information. One might express surprise that such items could be unknown to us, but anybody working in a library with a history will readily come to understand how that could happen.

CONCLUSION

In short, the conservation project has in my opinion more than proved its value. The Parliament did, after all, establish a National Library in order to place focus on our written heritage. I am happy that we managed to convince the Ministry of the need for the project, I am grateful that we have been given sufficient means to buy the necessary equipment to do a proper job, I am impressed with the efforts made from all our collaborators, both the permanent staff (it is not all that much fun to vacuum clean two hours a week for two years, or rewrap extremely dirty papers) and the personnel hired to do such work, I see the potential for making the collections more known to the country through digitizing and through the added value that a thorough insight in the collections has given us and I feel we can face the future with a clean, beautified façade under which huge quantities of exciting material is to be found.

As for the conversion project I believe the conclusion will be just as positive. It should be emphasized that both projects supplement each other. Without fully converted catalogues the thorough examination of the legal deposit collection will be of less value. Without a recataloguing of all our periodicals, we will still have to inform the audience that 'in theory we have everything, it just has not been put into a catalogue' and without a further conversion of the special catalogues, the information contained within the special collections will still have to be sought out in situ.

As mentioned, we originally outlined a two-phase project. With such splendid results, we hope the Board will grant us the possibility to complete the second phase so that the library can present itself to the nation in a thoroughly overhauled and modernized form

STATISTICS

The projects involved detailed statistics of all our collections, with special figures for book, periodicals, ephemera, posters etc. The surveys gave us a solid foundation upon which to draw our plans, both for conservation, for temporary moves and for the planning involved in organizing the new stacks. We also now have figures for lacunae (so far approximately 2.000 items identified), for conservation needs (estimated from 2-20 years of work, depending on level of repair).

However, I believe the figures of most interest to an external audience is the progress made during the project. Here are some figures of the status for the conserving project, as of 31.12. 2003

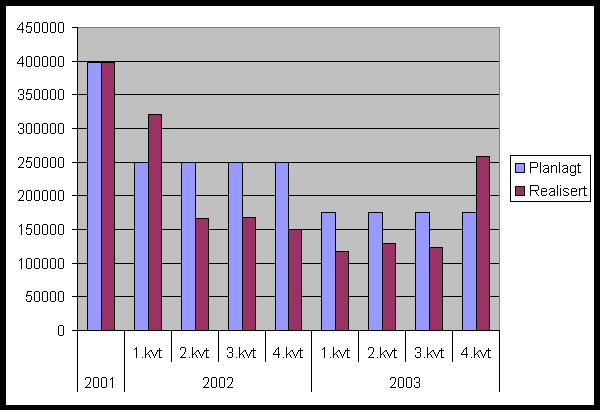

Figure 1: Number of items conserved quarterly. (Light blue is planned, red is actually conserved.)

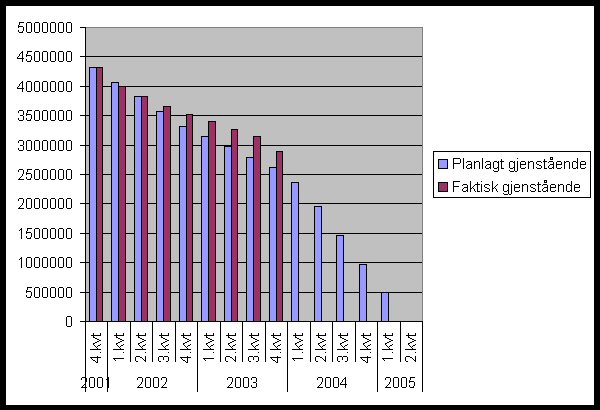

Figure 2 : Changes in the holdings of non-conserved documents.

What remains is partly to work through the backlog incurred during the move to the temporary site and to complete the rest before June 2004. The backlog is estimated to approximately five man-years and the rest of the planned production is estimated to 23 man-years.

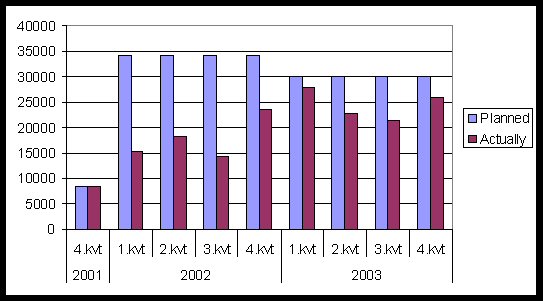

Figure 3: Number of items converted quarterly.

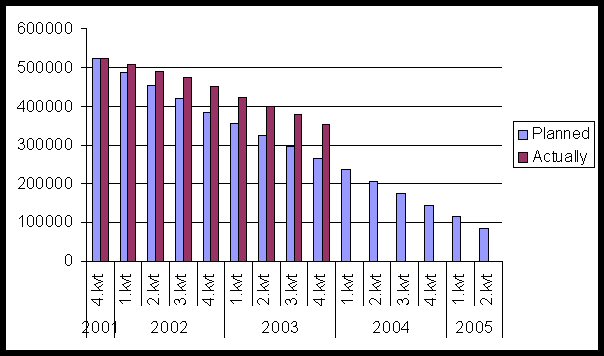

Figure 4: Total production of conversion quarterly.

WEB SITES REFERRED TO IN THE TEXT

National Library of Norway. http://www.nb.no/

Conservation project of the National Library. http://www.nb.no/html/konservering_av_samlinger.html

LIBER Quarterly, Volume 14 (2004), No. 1