In Europe we tend to think of cultural diversity as the very essence of our European fabric. This conference has also underlined the necessity for sticking to internationally recognised standards if we want a seamless cooperation in the future. So I believe that presenting the Danish situation to you serves a dual purpose: that of confirming that basically we do the things you do, but we also do some things in a different way which hopefully might be inspiring. I shall be looking at both aspects, with the main emphasis on the Danish models.

We share a library vision in Denmark – to a great extent. Certainly we agree on the cornerstones in it, and this vision is something we share with most of you. It is the vision of an actual hybrid library with vastly improved electronic services based on co-operation between public libraries and research libraries and – not least – co-operation between small and larger research libraries. We seek to combine a decentralised development with a national strategy and a national electronic library infrastructure. The Danish National Library Authority, which I represent, is a superinstitutional national body one of whose tasks is to develop national strategies and support co-operation between all types of libraries. Denmark has a population of 5 mio. and our strategy therefore has to contain close co-operation as a means to obtain a full-scale development of both service and collection building. We strongly believe that resource sharing is the basic element of high cost-effectiveness.

The tasks in question are linked to improved access and new services. Improved access is about easier access to more material for more people. New services mean i.a. electronic ordering and delivery, profile-based regular news selection and other value adding services, closer co-operation with users, consultative partnerships with various research projects, businesses and other segments. These services can be said to involve new roles and new partnerships in both well known and fresh contexts.

KEY FIGURES – MAIN STRUCTURE

In order to discuss the vision in earnest and comprehend its premises, you will need a few key figures as well as an outline of the structure.

Our official library statistics divide the research libraries into three main groups: 44 major research libraries, 180 university institute libraries and 144 minor research libraries. In organisational terms the 12 largest libraries form one group and the rest another. „Minor libraries“ indicate libraries with three staff members and less, so they are very small. The major libraries include one national library, five traditional libraries, 15 university college libraries and 23 special academic and training college libraries. To this list you may add a quickly growing number of libraries at upper secondary schools, business colleges, technical schools etc.

The picture is emerging of a closer co-operation than before. For example, the Danish National Library of Science and Medicine is at present acting as a library system host for 25 minor libraries in the health sector which opens the door to other kinds of co-operation as well. Another example is the growing integration of university institute libraries into major libraries, enabling them to offer new services and actually becoming real libraries. Yet another example is the quickly developing co-operation on networking such as building subject portals on the net.

Some of the biggest libraries, The Royal Library, The State and University Library, The National Library of Science and Medicine and some others are independent institutions under the Ministry of Culture. They all have a fouryear so-called performance contract with the ministry in which their objectives, tasks and priorities are stated.

The typical situation is, however, the one most of you are familiar with where the library is part of a parent institution with which it must negotiate its conditions. The three most important Danish ministries dealing with libraries are the ministries of culture, research and education.

DEVELOPMENT OVER THE LAST DECADE

The development is probably mirrored most clearly in the statistical analysis the Danish National Authority carries out annually of the 21 biggest research libraries covering a ten-year period.

To put it briefly: There has been a constant expansion in usage – in number of loans 160 %. Costs have increased – especially as regards serials, collections have increased slightly, there has been a growing demand for electronic services, a relatively stable economy and quite a stable number of staff. What the statistics don’t tell us at the moment, are the figures for the use of electronic services. Most libraries do some calculations, but it is not reflected in the official statistics in a standardised way. From this year, however, we have decided to set up official counting even if there is no international standard in this field – normally we stick to ISO-standards. We most certainly are in desperate need of performance measurements.

A glance at the graphs below will illustrate the situation more precisely than many words.

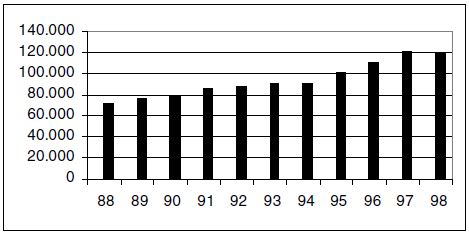

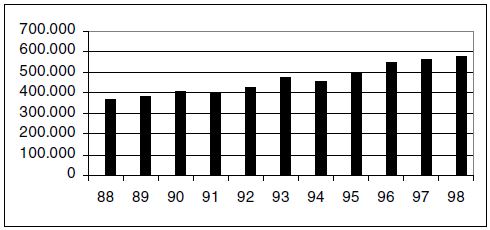

Fig. 1: All loans: 21 research libraries

Fig. 1 illustrates more than any other figure we know the expansion.

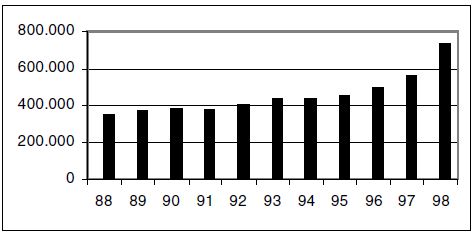

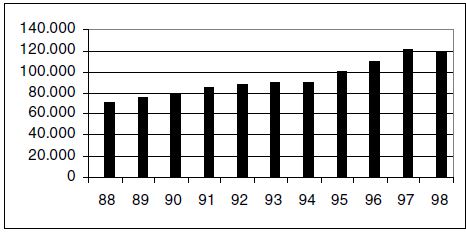

Fig. 2: All interlibrary loans

The figure is extremely high. This was very clearly brought home to us when we participated in the EU-libecon survey. The project managers twice asked us if the number of ILL was correct and how we defined it. We do, of course, follow the international definition and the figures are correct, which means that the Danish number of ILL is 25 times the average in EU. So we may conclude that our collections are heavily used, and I regard this as a success factor for the co-operating library service.

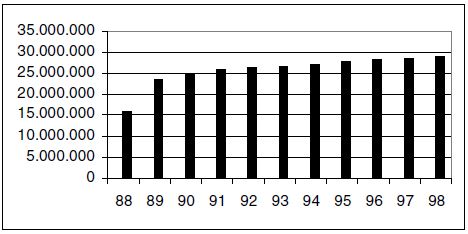

Fig. 3: Collections

The figures here are likely to change in the coming years with electronic services booming and traditional ones stagnating.

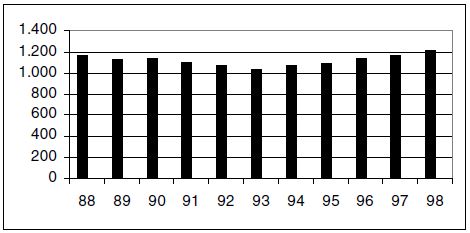

Fig. 4: Library staff

The stable number of staff members in the 21 biggest research libraries is about 1,200.

Fig. 5: Expenditure (1,000 ddk)

Fig. 6: Expenditure, stock, subscription etc.

CHALLENGES AND STRATEGIES

The challenges are to a large extent similar to those in other western European countries, and I have already mentioned the most important one: establishing a well-functioning hybrid library system, with a new form of co-operation, new services and new professional roles. The users and the library owners want a lot more for the same amount of money. The Danish National Library Authority runs a number of programmes in public and academic libraries that can be divided into four strategies:

- ICT-lift programmes aiming at Z39.50 based library systems, development of electronic services

- Rationalisation of structure due to better co-operative possibilities: integration of libraries, support to systems co-operation in research libraries as well as public libraries

- Skills development – a programme aimed at every public library is already running, and the academic libraries are beginning to follow suit

- Development of new services – which we support by distributing grants to various projects and by initiating services and the new basis for these.

ACT ON LIBRARY SERVICES

A new act on library services was passed by the Danish Parliament, Folketinget, in May 2000. The overall aim of the Act is to set a new standard for what a library actually is, namely a hybrid multimedia library with the emphasis on access – the connection concept being based on networking cooperation between libraries. This concept is not unfamiliar to large European research libraries, but the new standard – named the extended library in the Act - will apply to all libraries, even those in the smallest community. One of the backbones in the Act is ILL activities between research and public libraries, free of charge for the public libraries.

It was essential to determine a demarcation line between services which are free and services which may be charged for. The Act states that access to all media is free of charge in all libraries – with one exception. Libraries may charge users for access to licensed electronic material where the price is based on individual user consumption. But the main principle is that access to information is free while access to new and particularly time-consuming services will be charged for. It will for instance be possible to organise a chargeable instant-delivery service of printed material. Such a service appears natural in a library environment where you can search for and order library material from your home workstation. An instant digitise-on-demand service could likewise be set up – copyright legislation permitting.

Other chargeable services are linked to the learning library’s recent experience that instruction and consultancy activities are increasing in all types of libraries. Many libraries possess skills of considerable value in the workforce market place. Take a field such as updating homepages with relevant links – obvious as a new paid-for special library service.

The new Act also defines new frames for the library structure with closer cooperation within larger regions than today. Likewise it opens for co-operation between in particular smaller communities.

http://www.bibliotek.dk‐ FREE ACCESS FOR EVERYONE TO THE DANISH NATIONAL UNION CATALOGUE

In September 2000 the Danish libraries’ shared catalogue of holdings will be available to everyone via the Internet. This will provide every citizen in the country with equal opportunities for searching, finding and gaining access to information, and it will be possible to request books or articles (or other media) and collect them from your own library.

The Danish National Union Catalogue contains holdings information from nearly all Danish public libraries and most of the research libraries available to the public. This information is the basis for a new service: direct access for the end-user and the possibility of putting in requests. The database, called bibliotek.dk has more than 8 million records of materials in Danish libraries.

The user can search on three levels: simple search, advanced search and a blank CCL-screen and having selected a title, he must then choose a library to collect the material from. The user doesn’t have to select which library should provide the material – only where to collect it.

The request is sent from bibliotek.dk to the user’s own library either by e-mail (human readable or machine-readable), a web-based database of requests or in the near future by Z39.50.

If the library has got the material there is no problem. If it hasn’t, it will receive information about relevant libraries according to the Danish ethical rules for Interlibrary Loan. Executing a request for an ILL-request is only a click away on the web-based database of requests.

Some may think that these facilities are at a rather unambitious level, but we have settled for a technical level which is expected to run smoothly. Being able to check in bibliotek.dk whether the titled wanted is available at your local library would be an attractive service, but this will not be possible for another year or so when the Z39.50 has been further implemented.

Bibliotek.dk is the backbone of the Danish hybrid library model, and at the moment we are also designing a public library portal to be integrated into bibliotek.dk and the electronic research library portal. There are plans, too, for providing bibliotek.dk with booksellers’ data which means using the database even for buying books.

There will be a Danish and an English user interface on: http://www.bibliotek.dk

DENMARK’S ELECTRONIC RESEARCH LIBRARY (DEF)

I should now like to introduce you to a model which is concerned with the change of concept and of services in the research libraries. It is a national 5year project run by a steering group and a secretariat within the frames of the Danish National Library Authority and supported by three ministries to the extent of 200 mio. DKr.

An intriguing point about this project is that we don’t know where we will end! The aim of the project is to speed up the process of establishing a new set of library services, a new co-operation on electronic resources, new cooperative relations between the smaller and the larger libraries and preparing the ground for scholarly publishing and other relevant new library tasks. But as yet we do not know what kind of organisation will in time be running the electronic library. What we try to do is to combine a decentralised development of local library resources with national co-ordination and a national electronic library infrastructure.

DEF’s main components are national infrastructure (the research net having been chosen), library infrastructure (upgrading systems to Z39.50 standard), digital resources (mainly full text databases) and user facilities (print on demand facilities for instance).

Digital resources are the critical point. At the moment there is access to some 4,000 electronic journals and there is a programme for retroconversion of the last relevant catalogues. As far as digitising printed material is concerned, a priority has been decided upon, but very little actually done about printed bibliographic sources and journals. We are rather uncertain about the cost benefit of digitising older volumes of journals. You have to remember that the Danish academic population is small, and that a lot of the older research material will not become more relevant just because it has been digitised. At the moment I am more in favour of a solution such as digitising on demand or simply digitising the articles that are asked for – and directing our attention towards developing better bibliographic tools to the journal literature.

The architecture of the digital library is based on three cornerstones: the DEF-portal, -catalogue and -key.

The DEF-portal is at the moment a directory with access to the libraries’ own homepages, catalogues of the libraries’ holdings, digital material databases and subject-based links collection.

With the DEF-directory the route has been mapped out to DEF’s portal and from this general level the user can click his way straight into the libraries’ special collections.

Furthermore, a number of projects deal with developing subject portals: At the moment five portals are being designed to open in the autumn 2000: A portal to business economics, including business-relevant, descriptive statistics, a portal to the virtual music library, to medical clinical information, to food industry and finally to energy technology. The project groups have agreed on a metadata profile, developed quality criteria, have started collection and registration of resources and are now working together with users on the development of a user interface. A sixth subject portal will probably deal with - and be organised by - arts libraries.

At the moment there is also a project group working on testing crosssearching capabilities in different catalogues using the Z39.50 protocol. They are still experiencing difficulties with system vendors, and facilities for reserving materials and checking holdings are still to come, but progress is evidently being made every day.

The DEF-key is also an essential requirement of the whole project. A project group has analysed the possible solutions, a number of key specifications have been set up and tenders for the establishment of the key will be invited in autumn 2000. The core elements in the specifications are: access to resources independent of location, providing user identification to authenticate the user in relation to all DEF-libraries for determining their user privileges and decentralised registration and administration through a number of shared web-to-z gateways.

IMPORTANT LESSONS

So far we have learned some important lessons from our projects – especially from the electronic library project which looks like being a definite success. Most of the lessons may be very simple, but they are not self-evident.

In the Danish research library environment, which has been characterised by keen mutual competition and sometimes even conflicts at a personal level, it is important to agree on the major goals in the action plan of the project run by DEF. Such an agreement is the prerequisite for co-operating instead of fighting, and sufficient time has to be devoted to reaching a level of unity.

An equally simple line of thought propounds that the strong should carry the heavier load. This principle applies, for example, to libraries being willing to allocate some staff resources to project groups and delegate responsibility for current tasks. It also applies to the implementation of complex technical solutions. The principle is handsomely adhered to in the Danish National Library of Science and Medicine’s co-operation with the 25 minor libraries in the health sector, which do not only – at a reasonable price – get to share a library system, but are also provided with tailor-made advice and support in other areas, which means pulling in the small libraries as partners in the electronic library. I may even go a bit further and say that those who can and will carry should do so, which means that project groups could be redesigned and adapted till they work efficiently.

We have always chosen the line of least resistance when given the opportunity to allocate funds to libraries with enthusiasm and initiative. We did so to enable them to launch pilot projects and gain valuable experience for the sector. This lesson only makes sense, however, if you have some money, so another simple lesson is: pool enough resources to act. There are many ways of doing this - the toughest being pooling the resources individually allocated – or cutting a percentage off your budgets for a pool. In the short term it hurts – in the long term it may create miracles.

The last lesson I am going to mention is: If you go for a networking project like the Danish Electronic Research Library, make sure that the co-operating organisation, the secretariat or whatever acting body you have, can make decisions independent of single institutions. If you manage to do that you will be able to make decisions which are for the common good and in accordance with the overall objective, and that is essential if one is to move from a level of the success of individual institutions to a national sector’s effectiveness and ability to change.

Jens Thorhauge

Director General

Danish National Library Authority

Nyhavn 31 E

1051 Copenhagen K, Denmark